Helsinki was bombed several times during World War II by the Soviet Long-Distance Bomb Group Regiment (Russian: Avia Polk Dahl’nevo Deystviya—APDD), the largest of which took place during 1944, when Soviet Petlyakov Pe-8 Heavy Bombers flew 276 sorties against Helsinki, Tallinn and Pskov. In February 1944, 3 raids were undertaken by the Pe-8 over the city of Helsinki. The raid of the 06th of February 1944 was the largest, comprising 24 Pe-8 bombers from the 45th Division of the Long-Distance Bomb Group. During the second raid on the 07th of February 1944, two super-heavy 5.4 tonne FAB-5000 bombs were dropped on Helsinki, one destroyed the cable works, and the other struck the railway works.

When the Soviet Union attacked Finland during the autumn of 1939, Helsinki’s Air Defence was largely unprepared. The defence consisted of four heavy anti-aircraft gun batteries comprising three to four guns each (the 1st Anti-Aircraft Regiment); one light Anti-Aircraft Gun battery and one Anti-Aircraft machine gun Company.

In 1943 the command of Helsinki’s Air Defence was passed to Colonel Pekka Jokipaltio. Jokipaltio set about updating and strengthening the Air Defence system which was improved considerably under his command. During the Continuation War Germany provided two early warning radars and four gun laying radars to Helsinki. In addition, 18 German 88 mm Anti-Aircraft guns were placed in Lauttasaari, Käpylä and in Santahamina.

By February 1944 Helsinki was protected by 13 light and heavy Anti-Aircraft Gun batteries. Air defenses included 77 heavy Anti-Aircraft Guns, 41 light Anti-Aircraft Guns, 36 search-lights, 13 acoustic locators and 6 radars supported by visual spotters. The Air-Defence network was based on the German model and was considered extremely effective in countering the Soviet threat. In fact, when the Allied Control Commission visited Helsinki after the war, its leader Soviet General Andrei Zhdanov was extremely perplexed by the lack of damage.

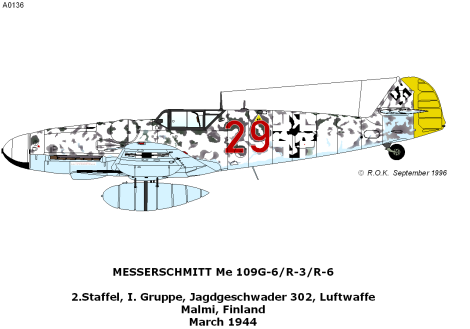

The Helsinki Air Defence system was supported by 12 German Messerschmitt Bf 109G-6/R6 Night-fighters of Jagdgeshwader 302 based at Malmi and the German Night-fighter Direction vessel (Nachtjagdleitschiff) Togo, From October 1943, Togo cruised the Baltic Sea under the operational control of the Luftwaffe‘s 22/Luftnachrichten Regiment 222. In March 1944, after the three great Soviet bombing raids on Helsinki, she arrived in the Gulf of Finland to provide night fighter cover for Tallinn and Helsinki.

Helsinki’s air defenses prioritized stopping bombs from reaching the city over the destruction of air targets. In a special type of barrage, several batteries would fire a wall of flak in front of the approaching bombers in an attempt to scare them into dropping their payloads too early and breaking away. Anti-Aircraft shells had been jury-rigged by drilling the fuse-hole larger and filling the extra space with magnesium mixed with aluminium, turning their explosion from a dull red to a searing white.

Civil defence was well organised and effective in Helsinki. Due to a far-sighted City decree in 1934, air raid shelters had been constructed in all high-rise building basements. All buildings were required to have an appointed civil protection supervisor who was not in the reserves or the armed forces, and as such was usually unfit for military service. This person was tasked to see that all occupants made it to the shelter in an orderly fashion.

There were a few larger shelters built into solid rock, but it was not possible to fit all the citizens of Helsinki into these. Some hospitals were also equipped with subterranean shelters where patients could be relocated during air raids. Others, such as the Children’s hospital, were moved outside the city. One hospital was entirely underground, below the Finnish Red Cross building. Much of the Air Defence system of Helsinki was operated by the City’s Citizen Volunteers which were drawn from organisations such as Suojeluskunta, which provided 16 year old male volunteers to man the Anti-Aircraft Guns and The Lotta Svärd organization, which provided Female volunteers to operate the Searchlight Batteries.

Soviet bombing raids on Helsinki during World War II have come to be known as “The Great Raids against Helsinki”. These began on the 30th of November 1939 just 3 hours into the Winter War. Helsinki was bombed a total of eight times during the Winter War. Some 350 bombs fell on the city, resulting in the deaths of 97 people and the wounding of 260. In all, 55 buildings were destroyed.

The Soviet bombings led to harsh reactions abroad. U.S. President Roosevelt asked the Soviets not to bomb Finnish cities. Molotov replied to Roosevelt: “Soviet aircraft have not been bombing cities, but airfields; you can’t see that from 8,000 kilometers away in America”. Molotov is said to have claimed that the Soviets were not dropping bombs but dropping food supplies to the city. The Finnish response was to develop the ‘Molotov Cocktail’ petrol bomb, said to have been so named as it was ‘the drink to go with the food that the Soviets have given us’.

Helsinki was bombed 39 times during the Continuation War. The majority of deaths and damage caused to the City were during the three big raids of 1944. 245 people were killed and 646 were injured from 25th June 1941 to the 19th September 1944.

| Raids | Bombs | Dead | Wounded | |

| Winter War | 8 | about 350 | 971 | 260 |

| 1941 | 9 | about 80 | 332 | 210 |

| 1942 | 17 | about 70 | 683 | 167 |

| 1943 | 13 | about 110 | 3 | 21 |

| 1 91 deaths on 30 November 1939 2 22 deaths on 9 July 1941 3 51 deaths on 8 November 1942 | ||||

The Great Raids of February 1944 consisted of three large-scale raids directed at the Finnish capital which were designed to break the resolve of the Finnish people, thus forcing the Finnish Government to the negotiating table in order to end the Continuation War. The raids were conducted on the nights of 6–7th, 16-17th and the 26-27th of February. Joseph Stalin had obtained British and American support for this measure at the Tehran conference in 1943. In this manner the USSR hoped to force Finland to break its ties with Germany and agree to a peace settlement.

Finnish air defense forces counted 2,121 bombers in the three raids of February 1944, which dropped more than 16,000 bombs. Of the 34,200 shots fired against the bombers, 21,200 were with heavy Anti-Aircraft Artillery, and 12,900 were with light Anti-Aircraft Artillery. The Finns deceived Soviet pathfinders by lighting fires on the islands outside the city, and only using the searchlights east of the city, thereby leading the pathfinders to believe that it was the city. Only 530 bombs fell within the city itself. The majority of the population of Helsinki had left the city, and the casualties were quite low compared to other cities bombed during the war.

Of the 22 to 25 Soviet bombers lost in the raids, 18 to 21 were destroyed by Anti-Aircraft Artillery fire, and four were shot down by German night fighters.

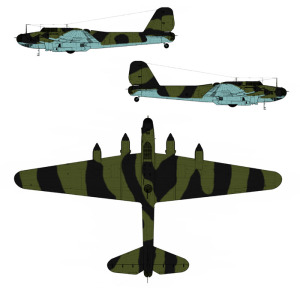

In addition to the four-engine Petlyavov Pe-8 heavy bombers, the APDD flew large numbers of twin-engined Ilyushin-4, Lisunov Li-2, North American B-25 Mitchell and Douglas A-20 medium bombers. The B-25s and the A-20s had been supplied to the Soviet Union under the Lend Lease programme from the United States. The Lisunov Li-2 was a Soviet bomber version of the American Douglas DC-3.

The first great raid: 6–7 February

The first night saw the most destruction.

The first bombs fell at 19:23. Some 350 bombs fell within the city and approximately 2,500 bombs outside of Helsinki. The total amount of bombs dropped (including the ones that fell into the sea) amounted to some 6,990. Approximately 730 bomber aircraft participated in the raid. The bombers arrived in two waves: 18:51–21:40 on the 06th of February, and 00:57–04:57 on the 07th of February.

The defense fired 122 barrages. The light Anti-Aircraft Artillery fired 2,745 shots and the heavy Anti-Aircraft Artillery fired 7,719 shots. The Finnish Air Force had no night fighters at this time.

100 people were killed, and 300 injured. More than 160 buildings were damaged. The Anti-Aircraft defenses had issued several false alarms in the days leading up to the raid, which had lowered the population’s reaction time considerably.

The second great raid: 16–17 February

After the first raid, a German night fighter group of 12 Messerschmitt Bf 109G-6/R6 fighters with special night fighting equipment of Jagdgeshwader 302 were transferred to the Helsinki-Malmi Airport from the Estonian front. These managed to shoot down six bombers during the following two raids. The anti-aircraft batteries fired 184 barrages and downed two bombers. Heavy Anti-Aircraft Artillery batteries fired 12,238 shots and light Anti-Aircraft Artillery batteries fired 5,709 shots.

Most of the population of Helsinki had voluntarily evacuated to the countryside and the remainder took to their shelters at the first warning. This reduced casualties significantly.

383 bombers participated in the second raid. 4,317 bombs fell on the city, the sea and in the surrounding area, only 100 bombs fell within the city. The warning was sounded at 20:12 and the bombers approached again in two waves: 20:12 to 23:10 on the 16th of February and 23:45 to 05:49 on the 17th of February. The first wave tried to concentrate the bombing by approaching from different directions. The second wave of aircraft came in smaller groups from the east. Finnish intelligence had intercepted messages one hour and 40 minutes before the raid and warned the air defence, which had time to prepare. The air defence sounded the warning 49 minutes before the raid. Radar picked up the first aircraft 34 minutes before the beginning of the bombings.

This time casualty figures were much lower: 25 died and 29 were injured. 27 buildings were destroyed and 53 were damaged.

The third great raid: 26–27 February

On the evening of 26th of February, a single Soviet reconnaissance aircraft was spotted over the city. It was a sign of the coming attack. The weather was clear, which helped the attackers. Again Finnish Radio Intelligence intercepted messages of the forthcoming raid, this time 1 hour and 28 minutes before the bombing would commence – although the Soviets tried to maintain radio silence.

Five minutes later, the air surveillance grid, manned by Lotta Svärd auxiliaries, reported approaching bombers. A silent alarm was sounded in the city in good time before the raid. Street lights were turned off, trams and trains were stopped and radio transmissions ended. Because these measures were taken, the enemy had more difficulty finding their target. Citizens proceeded to the shelters in a timely and orderly manner.

The first bombers were picked up by Finnish radar at approximately 18:30, 25 minutes before they would arrive. A few minutes later, the night fighters took off and flew to their pre-determined positions. The Anti-Aircraft Artillery had also been forewarned. The air raid warning was sounded at 18:45. Anti-Aircraft Batteries opened up at 18:53. At 19:07 the first bombs fell.

This last great raid differed from the two previous ones. The battle lasted for some 11 hours and was divided into three different phases. The first one was in the evening and lasted for four hours and concentrated the attacks against the city. The second one was mainly focused on the defending Anti-Aircraft Artillery, but with little success. The last wave hoped to finally flatten the city, but the majority of the aircraft turned away when met with fierce Anti-Aircraft Artillery barrages and night-fighters. The all clear signal was finally sounded at about 06:30 in the morning on the 27th of February.

The damage, compared with the first night, was limited: 21 people were killed and 35 wounded; 59 buildings were destroyed and 135 damaged.

The heavy Anti-Aircraft Artillery fired 14,240 shots and the light Anti-Aircraft Artillery 4,432 shots. Nine Soviet bombers were destroyed. 896 bombers participated in the raid on Helsinki. They dropped 5,182 bombs of which only 290 fell on the city itself.

The damage of the great raids

Thanks to the efficiency of the Anti-Aircraft Artillery and the deception measures that were employed, damage was limited. Only 5% of the bombs fell within the city, and some of these fell in uninhabited park areas causing no damage. In the order of 2,000 bombers participated in the three great raids on Helsinki and dropped approximately 2,600 tons of bombs. Of the 146 people who died, six were soldiers; 356 were wounded. 109 buildings were destroyed. 300 were damaged by shrapnel and 111 were set on fire. The Soviets lost 25 aircraft.

By comparison, Dresden was bombed on the 13th to the 15th of February 1945 by 1,320 bombers, which dropped 3,900 tons of bombs. This force was comparable to the total that attacked Helsinki, but the Dresden raid killed about 25,000 to 35,000 people and the city was almost completely destroyed.

After the war, the Allied Control Commission led by Soviet General Andrei Zhdanov visited Helsinki. Zhdanov was perplexed by the limited damage the city had sustained. The Soviet leadership thought that they had destroyed the city completely and that it was these bombings that had forced the Finns to the peace table.

Finnish response

The Finnish Air Force responded to the air raids with series of night infiltration bombings of APDD airfields near to Leningrad. The first of these tactical attacks was called “The Night of the Bombers” by their Finnish crews. Finnish bombers – Junkers Ju 88s, Bristol Blenheims, and Dornier Do 17s – either tailed or in some cases even joined formation with returning Soviet bombers over the Gulf of Finland and followed these to their bases. Kari Stenman and Kalevi Keskinen describe the action that took place: “On 25th February the air force CO ordered bomber squadrons PLeLv 42 and 46 to attack these bases under suitable conditions. The Russians were to be mislead by the Finnish bombers joining the formations at night over the Gulf of Finland, when returning, say from a mission to Helsinki. Bomber squadron 46 tested the new tactics on the night of 29th February. Four Dornier Do 17 bombers too off and joined a returning Russian bomber stream over the Gulf of Finland.

The bombers flew to Levashovo airfield and invidually bombed the lit airfield at 2230. The bomb rows hit parked aircraft and shelters. Several fires were built up and a strong explosion shook the airfield. The flak opened fire when the Finns were already on their way home.” Each Dornier Do 17 was equipped with 20 x 50 kg bombs with 0,08 second delay. When the bombers took off and flew towards the Gulf of Finland their own AA artillery at Kotka gave them a goodbye greeting, as they didn’t seem to know the identity of these strange bombers flying in middle of the night. The Finnish bombers navigated their way into middle of the Gulf of Finland, all lights off, looking for a suitable Soviet bomber formation… Finding one, the Finnish Dornier pilots joined the enemy bombers unnoticed, slowly creeping their way inside the Soviet formation.

It took a lot of skill and nerves (a lot of nerves, when thinking about it 60 years later) to stay in the formation, as the Soviet pilots might recognize the strange looking bombers at any moment. After all, the German built Dorniers had completely different outlooks to the Soviet bombers, consisting primarily of Li-2s, B-25s, IL-4s and A-20 Bostons, with two squadrons of heavy Pe-8s. After crossing the front lines the Soviet planes suddenly turned their navigation lights on, feeling safe over their own side of the front lines. With sudden inspirations the Finnish pilots followed the example. With all lights on the huge bomber formation consisting of both Soviet and Finnish bombers flew eastwards, more and more inside the enemy territory, shining brightly in the dark sky.

The Soviet bombers arrived at their home field and readied themselves for landing. The Finnish pilots kept their nerve – and actually joined the Soviet night bombers in their landing circuit, still with navigation lights on. One by one the Soviet bombers landed, with the rest – Finns included – approaching the field. The bombers circled the Soviet airfield, brightly lit in the winter night of the northern hemisphere, landing one by one. And finally – the last Soviet bomber had landed and the bright lights of the field welcomed the last four bombers seen circling in the landing pattern. But instead landing these bombers opened their bomb bays, throttled up and filled the field with 80 shrapnel bombs, filling it with destruction…. The sudden attack was immensely successful. With no warning given, the four Finnish bombers gained complete surprise and attacked the Soviet night bomber field with no opposition.

The Soviet anti-aircraft artillery didn’t have any time to react. The bombs hit the plane rows and plane shelters. Several fires and a large explosions were seen. Keskinen-Stenman comments: “Encouraged by the successes, all regiment squadrons were ordered on March 2nd to participate on large scale attack against Leningrad area airfields. The opportunity came on March 9th when APDD bombers returned from the bombardment of Tallinn, Estonian’s capital. Nineteen Finnish bombers from all four squadrons joined several formations between Seiskari and Kronstadt and followed the APDD aircraft to Gorskaya, Levashovo and Kasimovo airfields.”

After the huge success of these four bombers the whole bomber regiment was ordered to readiness. It took until March 9th until the weather and other conditions made new attack possible. The four bomber squadrons of Flying Regiment 4, the whole Finnish Air Force bomber command, sent total of 19 bombers (or 21, depending on source). 10 Blenheims, 5 Dornier Do 17s and 6 Junkers Ju 88s took off for their mission. Once again the bombers infiltrated the Soviet bomber formations. The Blenheims of PLeLv 42 (bomber squadron 42) followed the APDD from north of Seiskari. PLeLv 44 joined the Soviet bombers near Kronstadt fortress island with five Ju-88s. PLeLv 46 joined the Soviet bombers near Kronstadt with five Dorniers. And PLeLv 48s Blenheims followed the Soviet bombers from Kronstadt.

Tactics were similar to the previous mission. Either the bombers joined the Soviet formation and flew alongside them, with landing lights on and joining the landing pattern, or the Finns followed slightly behind. Surprise was total both ways, bombs started to rain on the Soviet airfields when the last bombers were still landing or taxiing on the field. Bombs and the shrapnel struck without warning, Soviet losses of material and personnel were high, as personnel were not sheltered. On some occasions the Finnish bombers attacked while landing operations were still in progress, this must have caused extreme confusion when the airfield defenders saw aircraft still circling the field and couldn’t know whether they are own bombers trying to land or if there are still more Finnish bombers ready to attack.

An example of the effectiveness of these attacks is the bombing of Gorskaja airfield by three Blenheims of PLeLv 48. The three bombers hit their target from 1400 meters, 2140-2145. The planes dropped 28 x 100 kg explosive and 16 x 15 kg firebombs. Hits were observed in the north side of the field with five planes burning. Two more planes were burning in southeast corner of the field, with one storehouse exploding. Paavo Alava, a Blenheim pilot from Bomber Squadron 42, was on the BL-151 on the attack at March 9th. He describes the mission: “Our five planes took off with bellies filled with shrapnel- and firebombs. The tension rose in the cockpit when we were over the Gulf of Finland looking for a suitable enemy formation. There they come! Several planes flying at 500 meters east of Seiskari island, flying eastwards. We performed a quick turn and then as quietly as we could, joined their formation. I could see clearly how the neighbor’s boy sat in his turret, carefree.

A small light was on, he must have already dreamed of the coffee waiting on the ground. There they go! Li-2s and so close that I could shoot them with my machinegun. Sure hit! But I must restrain myself – the mission would fail if they recognize us. Another Soviet bomber formation flew towards us from east – they’re going to bomb Tallinn… Here we were – red stars over Gulf of Finland, with blue swastikas in middle of them. We are over Kronstadt, when the Ruskie planes start flashing signals with red and white lights. We see responding signals from ground. I guess this is permission to come in and land… The planes turn north towards Gorskaja. It was interesting situation – Soviet lead bomber navigates the formation to their home field, which would soon be bombed by enemy bombers flying in the same formation.

The field appears – all lights on. Large numbers of planes are in the landing pattern and more in ground, our four Blenheims dropped their bombs from 1200 meters. One of our Bombardiers remarked “Best regards from the people of Helsinki”. I can see the explosions in the rows of bombers and aircraft shelters. A huge explosion takes place as the fuel storage tanks go up in flames and planes are burning on the ground. This was one of the most successful missions in the history of our squadron. Everything worked perfectly from the beginning to the end.”

Keskinen-Stenman: “At around 2130 they released the bombs on landing airplanes, parked aircraft and runways, causing huge explosions and numerous fires on all airfields. The attacks came as total surprises and only at Levashovo airfield the AAA was on alert, though did not inflict any damage. The airfield strikes continued. On April 4th 34 bombers attacked Kähy airfield north-east from Leningrad, where aerial reconnaissance had observed 57 aircraft. Bombs were dropped at 2030 causing huge explosions. 23 large fires were counted by the retreating bombers. Further strikes were flown during May.” Aarno Ylennysmäki was bombardier in PLeLv 48’s Blenheims and flew a mission in 3rd May against yet another Soviet airfield. He describes the mission: “Vector 270 degrees, five minutes to target, I heard on headphones. The pilot turned and matched altitude to ordered 2900 meters. Then he pushed throttles forward and accelerated to over 300 km/h. At that speed they’d stay a shorter time at the target area over the AAA fire. We would be the 2nd last wave. Behind us follows only the big Stukas, Ju-88s, with their 1000 kg bombs.

Now I saw the first bomb explosions ahead, from the first bomber wave. I took them as my target and then continued to give more exact commands to the pilot as we approached. Two degrees left, straight, one right, here we go, straight ahead. I could see a row of Soviet aircraft in the light from the other burning planes and the row was running straight on the aiming line of the mechanical bombsight. Then the line, aiming dot and the beginning of the plane row connected and I released the bombs. The plane wavered as it got lighter and the signal lights came on showing all the bombs had been released successfully. Only now I had time to watch out and noticed the anti-aircraft fire cloudlets around our plane. Aki, in his turret behind us, was watching downwards when he noticed that a searchlight was trying to find us. He called suddenly “DIVE!”. The pilot pushed his stick almost to the instrument panel and the plane dropped quickly almost thousand meters lower. Then he pulled back and leveled the plane at 1500 meters. The G forces pushed us to our chairs at almost three times our normal weight. A moment later Aki called that a night fighter had flashed past us, just lower. We kept sharp lookout but didn’t see it anymore. The whole regiment returned without any losses. The planes from Onttola base had landed at Immola. The chatter of almost 30 pilots filled the field and we found out, that an enemy night fighter had followed the bombers almost as far as Immola. Next day the Commander of the Air Force arrived to the base and awarded medals to a number of the crews”

Mr. Torsten Sannamo was radio operator / gunner at Bomber Squadron 42 in the time of these attacks. He participated in the bombing of Kähy airfield May 3rd 1944. Mr. Sannamo describes his attack: “Our squadron was the first to arrive to the target. Our bombing altitude was 3100 meters. The enemy AAA fire did not reach our altitude, at least in my case, and my pilot Akke dropped the bomb load on the barracks of the enemy base. From my turret I saw several fires coming up. Our squadron had two groups, both with five planes. Any attacking fighter would have been met with machine gun fire from five guns, but we didn’t see any fighters and we landed at our base at Värtsilä at 2200.” The night of May 18th saw the largest attack against any single target. 42 bombers took off, 41 bombed Mergino airfield right after midnight. The attack was lead by PleLv 44 with their 8 Junkers Ju 88s, with 2 firebomb torpedoes, 1 x 500 kg, 26 x 250 kg and 80 x 50 kg bombs.

Next in the target was PleLv 46 with 9 Dornier Do 17s, altitude 1500 meters, 120 x 50 kg and 30 x 100 kg bombs. Then came the Blenheims, first PleLv 42 with 13 Blenheims, then PleLv 48 with 12 Blenheims. 42 bombed from 1800 meters, PleLv 48 from 1600 meters. The first major night infiltration bombing took place on 9 March 1944 and they lasted until May 1944. Soviet casualties from these raids could not be estimated reliably, however, large scale raids on Helsinki by the APDD were stopped soon after these infiltration attacks began.

References

- Torsten A. Sannamo: Kundina hesassa flygaajana krigussa

- Jukka Piipponen: Onttolan punaiset pirutMäkelä, Jukka (1967). Helsinki liekeissä. Helsinki: Werner Söderström osakeyhtiö. p. 20.

- Keskinen-Stenman: Suomen Ilmavoimien historia 4 – LeR4

- Helsingin suurpommitukset Helmikuussa 1944, p. 22

- Jukka O. Kauppinen; Matti Rönkkö (2006-02-27). “Night of the Bombers”. Retrieved 2010-04-12. Cite uses deprecated parameters (

- P. Hirvonen: Raskaan sarjan laivueet

- help)Martti Helminen, Aslak Lukander: Helsingin suurpommitukset helmikuussa 1944, 2004, WSOY, ISBN 951-0-28823-3