In August 1914, seven airships were available to the German Army; four were deployed in the West and three in the East. Three of those assigned in the West attempted to bomb French military targets in daylight; they were all destroyed and it was immediately obvious that airships could not carry out any role during daylight.

The three airships in the East completed their first mission on 28 August 1914 – a bombing raid against the railway station at Mlawa. However, enemy action forced one down and the crew was taken prisoner. The Army airships were also in action in the south during the Romanian campaign of autumn 1916, when they conducted several strategic raids against Bucharest and the Ploesti area.

On the night of 31 January-1 February 1916, LZ 55 (LZ 85) raided the harbour at Salonika with 6,000kg of bombs, and the combat log demonstrates the surprise that could be affected with an attack from the air. It also gives an idea of the endurance that was required to conduct an operation of this nature on a sortie that lasted 18 hours.

The crew sighted Salonika, but south of the town, still over the sea, was a dense bank of clouds. The ship stopped south of Salonika in order to observe the harbour and the ships at the quays, and some darkened steamers and ships with lights set were discovered in the bay. LZ 85 headed for two probable transport vessels and then to the harbour moles with their ammunition storage facilities. Some 60kg bombs were aimed at the ships and there was one hit close to the starboard side of one large vessel. It was impossible to say if any of the unlit ships were damaged in the attack. Most of the GP [general purpose] bombs were released over the harbour and railway installations. Two of them detonated at the head of a mole and a further six in the inner harbour, and others hit the stores, causing huge explosions and possibly setting ammunition ablaze.

The last bomb was responsible for a fast-spreading fire. Altogether fourteen small bombs were dropped on military warehouses north-west of the town. Only a very few guns managed to engage the airship because its appearance came as a surprise to the forces based at Salonika. After that the ship left the Salonika area and returned the same way it had come…

On a return visit later that year, however, LZ 55 (LZ 85) was downed by ground fire, and the Army began to withdraw the craft from the theatre. After that, with the last one LZ 71 (LZ 101), leaving in September 1917. Some sorties were flown against the French towns of Nancy and Poperinghe in April 1915, but a change in the nature of the air war came in May when the first of the new improved ships, LZ 38, reached operational status. Following a change in German government policy, and in line with the strategic vision of Peter Strasser, the head of naval airships, the Army vessels joined their maritime counterparts in a strategic campaign. This operation and others like it carried out in 1915 were the first examples of strategic bombing in the 20th century. However, the Army had not completely abandoned the idea of using airships in a tactical role, as shown for the fighting for Verdun. Four ships were sent to support the ground attack on 21 February 1916, although only two craft survived.

Airships of the Reichskriegsmarine – naval airships

It had been envisaged that the role of the North Sea coastal bases and their complement of airships would centre on reconnaissance, and indeed throughout the course of the Great War some 220 such missions were carried out. However, given the refusal of the High Seas Fleet to involve itself with fleet actions against the British Grand Fleet (apart from minor engagements such as Dogger Bank and the large-scale fleet engagement at Jutland in 1916), these missions were not always of primary tactical or strategic importance, despite the usefulness of the data gathered. The improved vessels that came into service in 1915, the ‘M2’ and ‘P’ types, did, however, allow a different strategy to be contemplated: the strategic bombing of Britain.

The Strategic Campaign

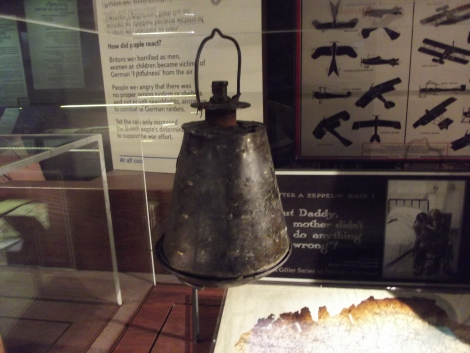

The night of 19-20 January 1915 ushered in a feature of 20th century warfare that was to become all too familiar: strategic air attack. The distinction between tactical and strategic warfare is sometimes indistinct – essentially it lies in the purpose of the attack. Tactical attacks are made with the intention of defeating a localized area, whereas strategic attacks aim to defeat states using a detailed plan, which typically attempts to defeat the enemy through political, military, and social means, and the denial of food, raw materials and supplies to industry. Those advocating of waging strategic warfare thus eschew Clausewitz’s maxim that advocates the necessity of defeating an enemy’s armed forces before victory can be achieved. This philosophy was grounded in 18th century experience – prior to the introduction of aerial warfare, an enemy’s armed forces usually stood in the way of waging war on infrastructure and population. By 1914, enemy forces could, for the first time, be bypassed without the need to defeat them or fix them in position, and a state’s civil population and infrastructure could be directly attacked. Another line of engagement or ‘front’ – the ‘Home Front’ as it later became known – had been introduced to warfare.

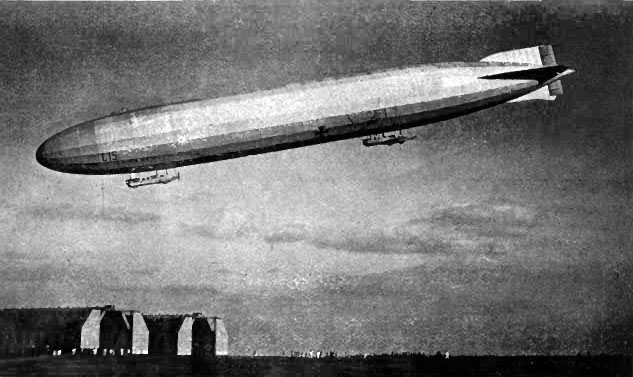

The first strategic air offence in history began somewhat inauspiciously on the night of 19-20 January 1915: two naval airships, LZ 24 (L 3) and LZ 27 (L 4), bypassed the battlefields of northern France, and crossed into Britain over Norfolk. They proceeded to drop bombs on areas that were lit up, presuming, correctly that they represented centres of population. L 3 hit Great Yarmouth and L 4 a number of East Anglian villages. Their tally for the night was four dead and 16 injured.

Further attacks over the following months were mainly, though not exclusively, aimed against targets in southern England, particularly London. The London raid occurred on the night of 31 May-1 June, with seven people being killed and only 30 injured. These attacks, and similar ones against France, such as that on 31 January 1916, when LZ 47 (LZ 77) attacked Paris with 2,000kg of ordnance, were against largely undefended targets. Having given notice of their intentions, though, this state of affairs could not be expected to continue, and the short period of darkness during summer time meant that the airship’s greatest asset, its invisibility, could be compromised. Accordingly, operations were largely suspended during the summer of 1915, with the plan being to resume them, with greater weight and effectiveness given the improved machines in the pipeline, during the autumn of that year.

Retaliation

That the British would take retaliatory measures became evident in April 1915 when Captain Lanoe G. Hawker, of the Royal Flying Corps based at Abeele in Belgium, flying a B.E.2c armed with a few bombs and hand grenades, attacked and destroyed the airship shed at Gontrode, within which, and also destroyed, was LZ38 (LZ38). It was an audacious attack, and highlighted just how vulnerable the airships were when on the ground.

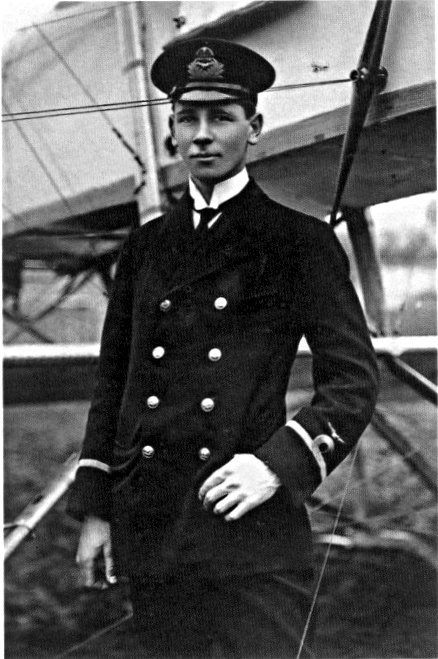

That they might be as vulnerable, given certain conditions, whilst airborne was graphically demonstrated on 6-7 June 1915, when Lt. R.A.J. Warneford Vc, of the RNAS was flying toward Ostend on his first ever night flight. His mission, emulating the earlier effort against Gontrode, was to bomb the Zeppelin sheds at Evere. Whilst en-route he spotted LZ37 (LZ37) in the clouds. Warneford maneuvered his plane over the vessel and released his bombs, one or more of which hit something solid. In any event there was a great explosion which ignited the gas, and the L37 (L37) fell earthwards engulfed in flames. This was the first time an airship had been destroyed by an aircraft whilst in flight.

Target London

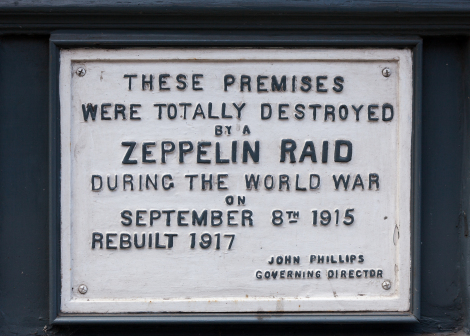

Strategic attacks in greater strength were resumed in September 1915, and below are extracts from the combat reports of LZ 44 (LZ 74), which raided London on the night of 7-8 September 1915, during the raid more than 4,800kg of bombs hit London, Middlesborough and Norwich, making it the heaviest raid directed against Britain during the First World War.

‘Departure 19.27 in the evening… LZ 74 crossed the British coast north of the Thames near Foulness Island. Only a few lights were visible on the ground and only a pale glow in the direction of the City of London when approaching at an altitude of about 3,200m. All the suburbs over which the airship passed were completely blacked out. Following the direction of the wind, and bearing in mind the known positions of British defences, the order was to attack London from the north when LZ 74 reached Brentwood-Woolford. Meanwhile the first searchlights were noticed…’

The account relates how, later, the commander of another airship on the sortie, SL II, mentioned that when the ship reached London, some ten minutes before LZ 74, only a few searchlights were in action. The staggered arrival of the aircraft had allowed the defences to mobilize. The log of LZ 24 (L 3), which was also on the raid, confirms this:

‘Navigation from Kings Lynn to London was straightforward because the landscape was completely dark and most of the cities were still lit up. London was still very brightly illuminated… Orientation over the entire capital was very easy because Regent’s Park was located precisely and the city centre was lit up as if in peace-time… the crew began dropping bombs near High Holborn at an altitude of about 2,500m’.

Despite being camouflaged the railway stations could be identified by the tracks leading to them, which were extremely difficult to conceal. One of these, identified as ‘Leyton railway station’, formed the first target, though it was only bombed to reduce the airship’s flying weight before moving onto the docks, the ‘main target’. There, it was estimated, bombs fell on the Surrey Commercial and, possibly, the West India Docks, as well as Bethnal Green Station. The apparent damage done and the response provoked were also recorded:

Large fires were visible from the sky. Between 12.54 and 01.50 the airship was engaged by several batteries, but without any success. One of the many incendiary shells, recognizable by their white smoke trails, passed by LZ 74 within a few metres before exploding about 400m above the ship. Both gunners, standing on top of the hull of the Zeppelin, took cover because some of the shells were so close.

Having dropped its bomb-load LZ 74 then headed back, leaving England ‘near the River Crouch’ and utilizing cloud cover to shield it from ground fire. The report admits that ‘there was no possibility of the commander and his men determining the actual position of the ship’. Which is evident of the somewhat primitive state of aerial navigation at that time. Nevertheless, the crew got their bearings after crossing the Channel and ‘landed at Namur at about 10.10’, with the only damage being ‘two hits’ on the structure and one engine which failed through ‘mechanical defect’.

1916

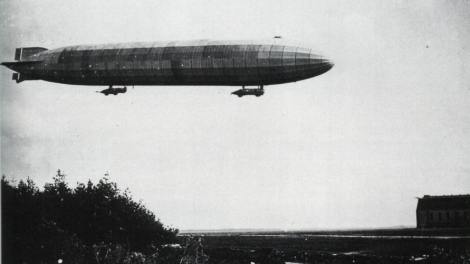

The year 1916 saw a greater effort to ‘Force England to her knees’ via war from the air. This was especially so when the first of the ‘R’ class airships, colloquially known to the British as ‘Super Zeppelin’, took to the skies with the commissioning of LZ 62 (L 30) and her induction into active service at the end of May. Sixteen of these vessels were to be completed before the end of the war, and they were to form an important part of the strategic offensive, though with decreasing chance of success as the British began to counter the attacks.

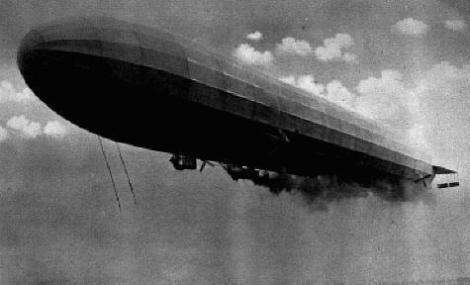

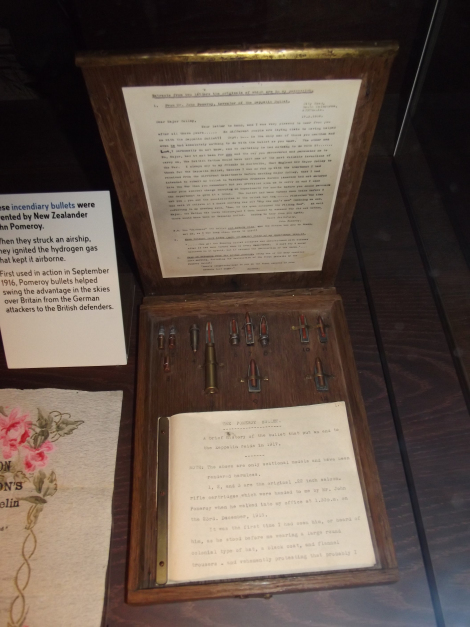

The development of aeroplanes technologically advanced enough to reach the altitude at which airships operated was not in itself enough to render the Zeppelins vulnerable; the aeroplanes also had to be equipped with ordnance that could exploit the flammable properties of the hydrogen gas. Each drum or belt of machine-gun ammunition carried a combination of ordnance: explosive rounds were combined with incendiary bullets. The explosive bullets would create holes in the hull and gas shells, whilst the incendiary rounds would ignite the escaping gas. This was successful and was graphically demonstrated by the spectacular destruction of SL 11, which was bad enough, but worse was to follow when ‘Super Zeppelins’ LZ 72 (L 31), LZ 74 (L 32) and LZ 78 (L 34) were destroyed by similar methods through September-November 1916.

After LZ 76 (L 33) was lost to anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) fire in September, the German high command realized that airships might not be capable of functioning in their allotted roles without improvement in performance. Indeed, many years later in 1934, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg revealed that von Zeppelin himself had confided to him in 1916 that, in his opinion, the airship was obsolescent and the future belonged to aeroplanes.

At the close of 1916 then, six airships had been lost in raids over Britain due to enemy action, and the Army was separately arriving at the same conclusion as von Zeppelin. Despite this, raids continued throughout the winter of 1916-17, and Strasser remained convinced that it was a worthwhile endeavour. He also attempted to find ways of improving the viability of the airships for waging his campaign.

1917

The only feasible improvement that could be made to airships in order for them to avoid destruction by fighter aeroplanes was to increase their operational altitude. As Strasser put it, ‘High altitude is the best defence against aeroplanes, and a greatly increased attack altitude is so necessary for further airship operations against England that all resulting disadvantages, including a reduction in speed, must be accepted’.

The reduction in speed came about because altitude in a given size of airship can only be traded off against weight, and it was decided to remove one engine from both LZ 80 (L 39), thus immediately saving some 1,750kg. In early February these vessels attained altitudes of over 5,000m. The first of the type to be manufactured, rather than extemporized, was LZ 91 (L 42), which was flight-tested on 28 February, achieving an altitude of some 6,000m. Known, for obvious reasons as ‘Height Climbers’ by the British, and designated as ‘S’ type by their opponents, these vessels formed the strategic striking force envisaged by Strasser until the last year of the war; the ‘R’ type were retrospectively modified to give them similar attributes.

Despite the fact that the ‘Height Climbers’ could operate outside the range of aircraft and AAA fire, they were not a great success, simply because of the hitherto unknown difficulties of operating at such altitudes. Neither humans nor machinery function properly in such cold, low-oxygen, environments, and the problems of predicting the weather so far above ground, together with the increased fragility of the lighter frameworks, made the high winds found in the sub-stratosphere dangerous. Navigation also became more problematic than before.

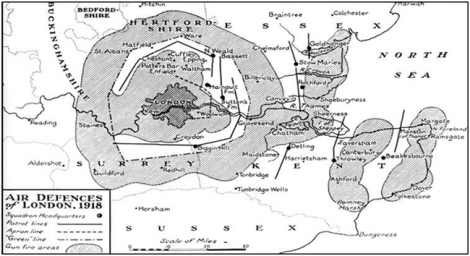

The first raid on England using high altitude airships, LZ 79 (L 41), LZ 80 (L 35), LZ 86 (L 39), LZ 88 (L 40) and LZ 91 (L 42), took place on the night of 16-17 March 1917. It was not a great success, and one ship was lost, mainly because of the effects of the weather. After ineffectually dropping six bombs on Kent, L 39 was driven off course by strong winds and then suffered apparent engine failure. The airship drifted over France at reduced altitude and was hit by AAA, which caused it to crash in flames near Compiègne. Despite the fact that the bombs dropped on southern England had caused almost no damage, the airships’ altitude gave them a certain invulnerability that concerned the British, whose defences appeared to have been ‘vertically outflanked’.

Further raids using altitude for protection took place on 23-24 May and 16-17 June, the latter raid caused severe damage as bombs hit (quite by chance), however, LZ 95 (L 48), one of the newer ‘U’ type vessels , got lost after dropping bombs in open countryside and reducing altitude from about 5,500m to 4,000m, an altitude where aeroplanes could operate. A British fighter climbed to within 150m and discharge a drum of anti-airship ammunition into the lower-stern of L 48 and the ship fell burning to the ground, though incredibly, three crewmembers survived.

Despite this loss, the raids continued, with attacks carried out on the night of 21-22 August and 24-25 September by eight and nine airships respectively. Neither of these produced any great results, with most of the bombs falling in open countryside. The intensity of the raids was stepped up with an 11 ship raid on the night of 19-20 October, but this was to end in disaster with the loss of five vessels, LZ 93 (L 44), LZ 85 (L 45). LZ 96 (L 49), LZ 89 (L 50) and LZ 101 (L 55), through the action of the poor weather at extreme altitudes. It seemed that in overcoming their first major technical difficulty, the flammability of hydrogen and the British ability to exploit it, the airships had fallen foul of the second, their inability to function against high winds because of the fragility of their design. This second problem was partially overcome by the introduction of engines that could maintain a decent output at altitude, though even these in LZ 105 (L 58) did not prevent the vessel having to abort a mission to bomb Britain on 12-13 December because of high winds.

1918

The first strategic raid of 1918 on Britain was on 12-13 March, using five of the latest airships. LZ 99 (L 54), LZ 100 (L53), LZ 106 (L 61), LZ 107 (L 62), and LZ 110 (L 63). The raid was rendered ineffective by the weather – not winds on this occasion, but rather thick cloud that obscured the ground. Another five-ship raid on 12-13 April was notable for the airship gunners hitting an aeroplane chasing their ship LZ 107 (L 62), and forcing it to break off and land. This successful instance of defensive gunfire is believed to have been unique, but an experiment that might have afforded a greater defensive capability had taken place on 26 January. The airship LZ 80 (L 35) took off with an Albatross D.III fighter suspended beneath it, which was successfully dropped from a height of some 1,200m, and flew safely away. The rationale behind this experiment is clear enough, but the project was not explored further.

The airship as a combat weapon was becoming obsolescent, though the tireless advocate of both the weapon and its strategic use, Peter Strasser, continued to deny this, and on 5-6 August himself led a five ship raid to bomb London. Strasser’s ‘flagship’ for this operation was the LZ 112 (L 70), the first ‘X’ type which had reached an altitude of some 7,000m during tests, whilst the other four ships, LZ 100 (L 53), LZ 103 (L 56), LZ 110 (L 63)and LZ 111 (L 65), had 6,000m ceilings. However, the defenders now deployed the two-seater De Havilland DH-4 aeroplane, which had a ceiling greater than 6,000m.

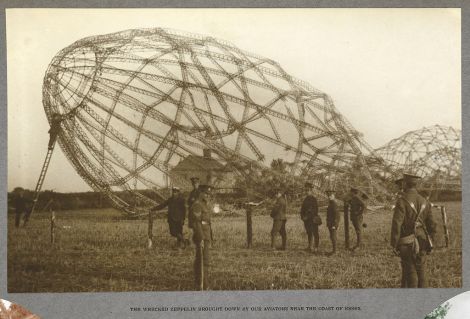

In any event and for unknown reasons, three of the airships, L 53, L 65, and L 70, chose to approach the British coast at heights of some 5,000m, where they were intercepted by three of the aeroplanes. The report of one pilot, Maj. E. Cadbury, graphically described what happened: ‘The [explosive bullets were] seen to blow a great hole in the fabric and a fire started which quickly ran along the entire length of the Zeppelin. The Zeppelin raised her bows as if in an effort to escape, then plunged seaward, a blazing mass. The airship was completely consumed in approximately 45 seconds.

The downed airship was L 70, and there were no survivors. Strasser had perished in Imperial Germany’s newest airship on what was to be the last strategic raid of the war. L 70 was not the last airship to fall victim to British fighters, however, on 11 August, while carrying out reconnaissance work over the North Sea, LZ 100 (L 53)was successfully intercepted by a Sopwith Camel launched from a lighter towed behind a destroyer. Despite operating at near maximum altitude (taking the aeroplane an hour to climb anywhere near it), the airship was ignited by gunfire from some 100 metres below, and plunged into the sea.

The airship as a weapon of war had clearly been neutralized, and in any event the defeat of German arms of all kinds was acknowledged within three months by the signing of the armistice. Nevertheless, high altitude strategic bombing had arrived.

References

- Boulton, James T., ed. The Selected Letters of D. H. Lawrence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University, 2000. ISBN 978-0-52177-799-5.

- Boyne, Walter J. et al. Air Warfare: An International Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio, 2002. ISBN 1-57607-345-9.

- Castle, Ian. London 1914–17: The Zeppelin Menace. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84603-245-5.

- Cole, Christopher and Cheesman, E. F. The Air Defence of Great Britain 1914–1918. London: Putnam, 1984. ISBN 0-370-30538-8.

- Cross, Wilbur. Zeppelins of World War I. London: Paragon House, 1991. ISBN 1-56619-390-7.

- de Syon, Guillaume. Zeppelin!: Germany and the Airship, 1900–1939. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8018-6734-7.

- Dooley, Sean C. “The Development of Material-Adapted Structural Form.” Part II: Appendices, THÈSE NO 2986. École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, 2004.

- Eckener, Hugo, translated by Leigh Fanell. Count Zeppelin: The Man and His Work. London: Massie, 1938 – (ASIN: B00085KPWK) ( extract pp. 155–157, 210–211).

- Lehmann, Ernst A. (1927). The Zeppelins. The Development of the Airship, with the Story of the Zepplins Air Raids in the World War. trans. Mingos, Howard. New York: J. H. Sears.

- Liddell Hart, B. H. A History of the World War 1914–1918. London: Faber & Faber, 1934.

- Robinson, Douglas H. Giants in the Sky: History of the Rigid Airship. Henley-on-Thames, UK: Foulis, 1973. ISBN 978-0-85429-145-8.

- Robinson, Douglas H. The Zeppelin in Combat. Henley-on-Thames, UK: Foulis, 1971 (3rd ed.). ISBN 0 85429 130 X.

- Smith, Peter J. C. Zeppelins over Lancashire. London: Neil Richardson, 1991. ISBN 1-85216-066-7.

- Stephenson, Charles. Zeppelins: German Airships, 1900–40. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2004. ISBN 1-84176-692-5.

- Swinfield, J. Airship: Design, Development and Disaster. London: Conway, 2012. ISBN 978 1844861385

- Vissering, Harry A. (1922). Zeppelin; the Story of a Great Achievement. Chicago: Wells and company.

- Willmott, H.P. First World War. London: Dorling Kindersley, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7195-6245-7.