Unternehmen Weserübung was the code-name given to the German assault on the countries of Denmark and Norway. Sweden would ultimately play a pivotal role in the conflict as would Finland whose war with the Soviet Union on the 30th November 1939 would have a direct influence over the decision of the German High Command to prosecute this campaign and would draw the Russians into an ideological power struggle with Nazi Germany culminating in Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union by the Axis powers. Britain and France would become directly involved in this ‘Scandinavian War’ the victor of which would control the mineral rich resources of the region.

At 04:15 (05:15 ‘Weser time’ or German time) on the 9th April 1940 (Wesertag; “Weser Day”), Germany invaded Denmark and Norway. The political motives behind this offensive were said to be a preventative tactic against a Franco-British occupation of Norway which had been openly discussed by the Governments of both countries.

The German Ambassadors to both Norway and Denmark informed the administrations of each nation that the Wehrmacht had come to ‘protect’ their National neutrality against Franco-British aggression.

Political and military background of the operation

During the spring of 1939, the British Admiralty began to consider the possibility of using Scandinavia as a potential theatre of war with Germany. A continental land battle had been ruled out by the British government due to the conceivable repetition of the First World War. Therefore a blockade strategy was considered in order to weaken Germany economically, using the vastly superior resources of the Royal Navy to deny Germany iron ore from the Swedish mining district upon which it was heavily dependent. Much of this ore was shipped through the northern Norwegian port of Narvik during the winter months, therefore control of the Norwegian coast was considered vital in the enforcement of a blockade against Germany.

Großadmiral Erich Raeder, the chief of the German Kriegsmarine became concerned that the British occupation of Norway posed an unacceptable risk to Nazi Germany. In October 1939, he discussed his concerns with Adolf Hitler, further arguing that should Germany possess Norwegian Naval bases before the British, they could threaten merchant shipping to the United Kingdom through a concerted submarine campaign thereby severely disrupting vital British trade. Hitler was not interested, having just issued a directive stating that the main military effort would be a land offensive through the Low Countries with an attack on France being the ultimate objective of the German armed forces.

Operation Wilfred, the proposed anti-ship mining of Norwegian waters, was suggested by Winston Churchill, then a new member of the British War Cabinet toward the end of November. The enterprise was designed to force Swedish and Norwegian ore transports through the open waters of the North Sea where they would be intercepted by the Royal Navy thus denying Germany vital supplies. It was intended that such a move would provoke a German response in Norway. Any German incursion into neutral Norway would provoke the Allies into implementing Plan R4 and occupy Norway themselves.

Though later implemented, the plan was initially rejected by Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax, due to a fear of an adverse reaction amongst the neutral nations, in particular the United States. Churchill proposed the plan once again after the Soviet Union had attacked Finland on the 30th November 1939. The mining scheme was denied once again.

In December shortly after the invasion of Finland by the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and France began serious planning for sending aid to Finland. The plan called for a force to land at Narvik in northern Norway, the main port for Swedish iron ore exports, and to take control of the Malmbanan railway line from Narvik to Luleå in Sweden on the shore of the Gulf of Bothnia. Conveniently, this plan also would allow the Allied forces to occupy the Swedish iron ore mining district. The plan received the support of both Chamberlain and Halifax. They were counting on the cooperation of Norway, which would alleviate some of the legal issues; however, strongly negative reactions in both countries curtailed its implementation. Planning for the expedition continued, but the justification for it was removed when Finland sued for peace in March 1940.

When the Soviet Union attacked Finland on the 30th November 1939, the Allies (principally the British and the French) found themselves allied to the Swedish and the Norwegians in support of Finland against the Soviet Union which was still subject to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and thus an ally of Nazi Germany.

In response to the Soviet attack, the Norwegians mobilized 9,500 troops of the 6th Division to Finnmark and Troms. The mobilization had been largely completed by the beginning of 1940. Curiously, part of the 6th division remained in the Eastern regions of Finnmark after the German attack in the event that the Soviets should strike.

During the Winter War both Norway and Sweden exercised ‘non- belligerence’ in direct contravention of their neutrality by sending troops, weapons and supplies to Finland. Sweden sent money, food, 135,000 rifles, large quantities of ammunition, 330 artillery pieces, approximately 8,700 volunteers and the Swedish Voluntary Air Force – Flygflottilj19, which consisted of 12 Gloster Gladiator fighters and 5 Hawker Hart Bombers all crewed by Swedish volunteers.

Norway sent a shipment of 12 Ehrhardt 7.5cm Model 1901 artillery pieces and 12,000 shells. In addition the Norwegian Government allowed the British to use Norwegian territory to transit aircraft and other weaponry to Finland.

Whilst the Allies were genuinely sympathetic to Finland, these events also presented them with an opportunity to send troop support to Narvik to occupy the iron ore fields in Sweden and ports in Norway.

The plan, prepared by British General Edmund Ironside, included two divisions landing at Narvik, five battalions in mid-Norway and a further two divisions at Trondheim. The French were keen to push for this action to divert German attention from France.

The landings in Norway by the British caused the Germans concern. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had placed Finland within the Soviet sphere of interest, and the Germans therefore claimed neutrality in the conflict. This policy caused a rise in anti-German sentiment throughout Scandinavia, since it was commonly believed that the Germans were allied with the Soviets. The German high command became concerned that Norway and Sweden would allow Allied troops to cross their territory to aid Finland.

The proposed Allied deployments of troops never occurred. Protests from both Norway and Sweden, due to the contravention of their neutrality, denied the Allies access to Finland. With the Moscow Peace Treaty on 12 March 1940, the Finland-related Allied plans were dropped. The abandonment of the planned landings put immense French pressure on Neville Chamberlain’s British government, and eventually led to the Allied mining of the Norwegian coast on 8 April.

While Germany and Sweden pressured Finland to accept peace on unfavorable conditions, Britain and France had the opposite objective. Different plans and figures were presented for the Finns. At first, both France and Britain promised to send 20,000 men who were to arrive by the end of February. By the end of that month, Finland’s Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Mannerheim, was pessimistic about the military situation. Therefore, on 29 February the government decided to start peace negotiations. That same day, the Soviets commenced an attack against Viipuri.

When France and Britain realized that Finland was considering a peace treaty, they gave a new offer of 50,000 troops, if Finland asked for help before 12 March. Through Soviet agents in the French and British governments, indications of Franco-British plans reached Stalin, and may have contributed heavily to his decision negotiate an armistice with the Finnish government on March 13th 1940.

The Economic Importance of Swedish Iron Ore during WWII

Swedish iron ore was an important economic factor in the European Theatre of World War II. Both the Allies and the Third Reich were keen on the control of the mining district in northernmost Sweden, surrounding the mining towns of Gällivare and Kiruna. The importance of this issue increased after other sources were cut off from Germany by the British sea blockade during the Battle of the Atlantic. Both the planned Anglo-French support of Finland in the Winter War, and the following German occupation of Denmark and Norway, were to a large extent motivated by the wish to deny their respective enemies iron critical for wartime production of steel.

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty was particularly concerned about Swedish exports of iron ore to Germany, and pushed for the British government to take military action to end the trade. From the beginning of the war Churchill tried to persuade his cabinet colleagues to send a British fleet into the Baltic Sea to stop shipping reaching Germany from the two Swedish iron ore ports, Luleå and Oxelösund. The project was called Project Catherine and was planned by Admiral of the Fleet William Boyle, 12th Earl of Cork. However, events overtook this project and it was canceled. Later, when the Baltic ports froze over and the Germans began shipping the iron ore from the Norwegian port of Narvik, Churchill pushed for the Royal Navy to mine the west coast of Norway to prevent the Germans travelling inside neutral territorial waters to escape Allied Contraband Control measures.

Background

At the outbreak of World War II on 3rd September 1939, Britain and France enacted a naval blockade of Germany similar to the blockade initiated with great success during the First World War. Germany, a country lacking in natural resources and heavily reliant on large scale imports of a wide range of goods was heavily reliant on mercantile trade. Perhaps the material Germany needed above all others was iron ore, a steady supply of which was imperative in the creation of steel to sustain her war effort and general economy.

In 1938, Germany imported 22 million tons of iron ore from various foreign sources. She was able to produce 10 tons of her own iron ore each year. This was however of low-grade quality and needed to be mixed with superior grade material from countries such as Sweden, which supplied Germany 9 million tons annually. 7 million tons of the Swedish ore came from Kiruna and Gällivare in Lapland and 2 million from the central Swedish ore field’s north-west of Stockholm.

With the outbreak of war, Germany lost approximately 9 million tons of iron ore per annum. She still had access to 3 million tons from Norway and Luxembourg; in addition 10 million tons per year were available from Lorraine in France. Supplies from Morocco and Spain were no longer accessible due to the British presence in Gibraltar, which meant that the remaining supplies available from neutral Scandinavia became crucial.

Grand Admiral Raeder, head of the German navy, declared that it would be “utterly impossible to make war should the navy not be able to secure the supplies of iron-ore from Sweden”.

Britain also relied heavily on large quantities of imported iron ore. The Royal Navy routinely stopped ships of all nations for inspections to ensure that they were not delivering important supplies to the enemy. Germany considered the Franco-British blockade to be illegal and therefore embarked upon a system of unrestricted submarine warfare. All vessels whether enemy or neutral could be attacked. This policy continued for the first nine months of the war resulting in a considerable loss of life.

The French and the British Fleets exercised a policy of leniency towards neutral vessels in an effort not to alienate them. The Allies were keenly aware that to not do so could result in sympathy for the German people and that many neutral mariners relied on Germany for trade.

Iron ore routes

There were two main routes by which iron ore was shipped to Germany from Sweden.

The Eastern Route

From May to November, iron ore from the Northern region was shipped from the port of Luleå down the Gulf of Bothnia to the German north Baltic ports at Lubeck, Swinemunde, and Stettin. From December to April, the Gulf of Bothnia froze over, severely restricting supplies, and although an alternate port was available at Oxelösund, south of Stockholm for the transport of iron ore from the mines in Bergslagen, this facility was unable supply the full amount required by Germany, and in any case froze over itself from January to March each year. Luleå remained outside the reach of Royal Navy’s patrols but it was estimated that when Luleå and the Baltic ports of Oxelösund and Gävle were open it could only supply around 8million tons, or less than half of the pre-war imports.

This meant that during the early winter months of the war, Germany had no choice than to transport the majority of its ore along the much further route down Norway’s heavily indented Western coast from Narvik

The Western Route (“Norwegian Corridor”, Western Leads or Skjaergaard)

The port of Narvik, high above the Arctic Circle was open for iron ore shipments all year round. But the stormy Atlantic coast of Norway also provided another extremely useful geological feature for Germany in her attempts to continue shipping the ore and beating the allied blockade.

Immediately offshore from Norway’s western coast lies the Skjaergaard (Skjærgård), a continuous chain of some 50,000 glacially formed skerries (small uninhabited islands) sea stacks and rocks running parallel to the shore. A partially hidden sea lane (which Churchill called the Norwegian Corridor) exists in the area between this rocky fringe and the coastal landmass proper. Inside this protected channel it is possible to navigate the entire 1,600 km length of the Norwegian coast from North Cape to Stavanger. Such coastlines, sometimes known as Leads — a rough English translation for the common Norwegian nautical term Ledene (shipping lane) are common around Scandinavia — Skjaergaard also exist along the Swedish and Finnish Baltic coasts and off Greenland.

The Germans made great use of the Norwegian Corridor to avoid the attention of the vigilant Royal Navy and RAF. In the winter of 1939–1940 a steady stream of their specially-constructed iron ore vessels made the long trip south from Narvik, sometimes within the three mile curtilage of neutral Norwegian territorial waters, sometimes just outside if the way appeared hazardous or the sea particularly turbulent. At the southernmost point the iron ore captains had to make a choice:

- Follow the Skjaergaard around the coasts of Norway and Sweden, down through the Kattgat and finally into the north German Baltic ports of Lubeck and Stettin. This route was safer because it brought them much closer to the protection of the German naval patrols and Luftwaffe air cover but involved hauling the very bulky and heavy iron ore the long way overland to the industrial centres on the overburdened German railway system.

- Leave the safety of the Skjaergaard and make a dash south across the Skagerrak, (the sea channel north of the Danish Jutland peninsula) and dash down the west coast of Denmark to Hamburg and Bremen. This was the preferred route because it allowed the ore to be taken straight along the efficient inland waterways to the industrial heartlands of the Ruhr and the Rhineland where it could be processed. It was much more hazardous, putting the ships and their cargo at the mercy of allied submarines and patrolling destroyers of the Contraband Control. A number of German ships were sunk in this area.

British attempts to disrupt German-Swedish trade

From the beginning of the war, Winston Churchill expended considerable energies trying to persuade his colleagues in the British government to take action to stop the iron ore traffic. On 16 December 1939 he issued a memo to the cabinet:

‘It must be understood that an adequate supply of Swedish iron ore is vital to Germany…the effectual stoppage of the Norwegian ore supplies to Germany ranks as a major offensive operation of the war. No other measure is open to us for many months to come which gives so good a chance of abridging the waste and destruction of the conflict, or of perhaps preventing the vast slaughters which will attend the grapple of the main armies. The ore from Luleå (in the Baltic) is already stopped by the winter ice, which must not be broken by the Soviet ice-breaker, should the attempt be made. The ore from Narvik must be stopped by laying successively a series of small minefields in Norwegian territorial waters at the two or three suitable points on the coast, which will force the ships carrying ore to Germany to quit territorial waters and come on to the high seas, where, if German, they will be taken as prize, or, if neutral, subjected to our contraband control’.

Although in late 1939 many of Churchill’s cabinet colleagues agreed with the need to take action to disrupt the iron ore traffic, they decided against the use of mines. At the time negotiations into the British chartering of the entire Norwegian mercantile shipping fleet were at a delicate stage and the British Foreign Office made convincing arguments against breaking Norway’s neutrality. In 1915 (during WWI) Britain had been forced to apologise to Norway for the violation of her territorial waters by British warships following the seizure of a German steamer inside the three mile limit. Near the end of WWI the British, Americans and French had induced the Norwegians to allow the Skjaergaard to be mined in order to prevent German ships and submarines from using their territorial waters as a way around the Great Northern Barrage, a massive minefield laid from Scotland to Norway as part of the earlier allied blockade strategy.

Despite the ongoing diplomatic exchanges, Britain informed the Norwegians that the Skjaergaard was about to be mined in January 1940, but the plan was postponed following protests from both Norway and Sweden. Yet another diplomatic dispute over alleged abuse of Norway’s territorial waters broke out in February 1940 between the respective governments of Britain, Norway and Germany following the Altmark Incident. A German tanker, attempting to return home via the cover of the Norwegian Corridor carrying British prisoners of war was spotted by British aircraft and pursued by destroyers, eventually being forced onto rocks.

On the evening of 21 March 1940 the British submarine HMS Ursula, (which had damaged the German cruiser Leipzig in Heligoland Bight the previous December) intercepted the German iron ore ship Hedderheim, en route from Narvik, and sank her eight miles off the coast of Denmark, although the crew were all saved. At the time it was seen as an early indication that Britain was at last taking steps to end the iron ore trade and over the next few days several other German ships were sunk at the entrance to the Baltic. Following reports that strong British destroyer and submarine forces were stationed in the Skagerrak, Berlin ordered all her ships along the iron ore route to port immediately.

By now it was clear to all concerned that the Phoney War was about to end. Antagonized by the German mining of their own waters with deadly new magnetic mines and a general concern that Germany was managing to overcome the worst effects of the blockade, the Supreme War Council met in London on 28 March 1940 to discuss an intensification of the economic warfare strategy.

Finally, on 3 April the War Cabinet gave authorization for the mining of the Skjaergaard. On the morning of Monday 8 April 1940 the British informed the Norwegian authorities of its intentions, and despite Norwegian protests and demands for their immediate removal, the Royal Navy carried out Operation Wilfred. However, by the time it took place German preparations for the German invasion of Norway were well under way and because of this only one minefield was actually laid, in the mouth of Vestfjord leading directly to Narvik.

Planning the Invasion

Convinced of the threat posed by the Allies to the iron ore supply, Hitler ordered Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Armed Forces High Command; OKW) to begin preliminary planning for an invasion of Norway on 14 December 1939. The preliminary plan was named Studie Nord and only called for one army division.

Between 14 and 19 January, the Kriegsmarine developed an expanded version of this plan. They decided upon two key factors: that surprise was essential to reduce the threat of Norwegian resistance (and British intervention); the second to use faster German warships, rather than comparatively slow merchant ships, as troop transports. This would allow all targets to be occupied simultaneously, as transport ships only had limited range. This new plan called for a full army corps, including a mountain division, an airborne division, a motorized rifle brigade, and two infantry divisions. The target objectives of this force were the following:

- The Norwegian capital Oslo and nearby population centres

- Bergen

- Narvik

- Tromsø

- Trondheim

- Kristiansand

- Stavanger

The plan also called for the rapid capture of the kings of Denmark and Norway in the hopes that would trigger a rapid surrender.

On 21 February 1940, command of the operation was given to General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst. He had fought in Finland during the First World War and was familiar with Arctic warfare. But he was only to have command of the ground forces, despite Hitler’s desire to have a unified command.

The final plan was code-named Operation Weserübung (“Exercise on the Weser“) on 27 January 1940. The ground forces would be the XXI Army, including the 3rd Mountain Division and five infantry divisions, none of the latter having yet been tested in battle. The initial echelon would consist of three divisions for the assault, with the remainder to follow in the next wave. Three companies of paratroopers would be used to seize airfields. The decision to also send the 2nd Mountain Division was made later.

Almost all U-boat operations in the Atlantic were to be stopped in order for the submarines to aid in the operation. Every available submarine—including some training boats—were used as part of Operation Hartmut in support of Weserübung.

Initially, the plan was to invade Norway and to gain control of Danish airfields by diplomatic means. But Hitler issued a new directive on 1 March that called for the invasion of both Norway and Denmark. This came at the insistence of the Luftwaffe to capture fighter bases and sites for air-warning stations. The XXXI Corps was formed for the invasion of Denmark, consisting of two infantry divisions and the 11th motorized brigade. The entire operation would be supported by the X Air Corps, consisting of some 1,000 aircraft of various types.

Preliminaries

In February, the British destroyer HMS Cossack boarded the German transport ship Altmark while in Norwegian waters, thereby violating Norwegian neutrality, rescuing POWs held also in violation of Norwegian neutrality (the Altmark was obliged to release them as soon as she entered neutral territory). Hitler regarded this as a clear sign that the UK was willing to violate Norwegian neutrality, and so became even more strongly committed to the invasion.

On 12 March, the United Kingdom decided to send an expeditionary force to Norway just as the Winter War was winding down. The expeditionary force began boarding on 13 March, but it was recalled—and the operation cancelled—with the end of the Winter War. Instead, the British cabinet voted to proceed with the mining operation in Norwegian waters, followed by troop landings.

The first German ships set sail for the invasion on 3 April. Two days later, the long-planned Operation Wilfred was put into action, and the Royal Navy detachment—led by the battlecruiser HMS Renown—left Scapa Flow in order to mine Norwegian waters. The mine fields were laid in the Vestfjorden in the early morning of 8 April. Operation Wilfred was over, but later that day, the destroyer HMS Glowworm—detached on 7 April to search for a man lost overboard—was lost in action to the German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and two destroyers belonging to the German invasion fleet.

On 9 April, the German invasion was under way and the execution of Plan R 4 was promptly started.

Invasion of Denmark

Strategically, Denmark’s importance to Germany was as a staging area for operations in Norway, and of course as a border nation to Germany which would have to be controlled in some way. Given Denmark’s position in relation to the Baltic Sea, the country was also important for the control of naval and shipping access to major German and Soviet harbours.

The German plans for the invasion and occupation of Norway relied heavily on air power. In order to secure the Skagerrak strait between Norway and Denmark, the air bases in Denmark had to be seized. The domination of this strait would prevent the Royal Navy from interfering with the main supply lines of the invasion forces. In this respect, the occupation of Denmark was considered to be vital. The capture of Aalborg Airport was considered as particularly important in this respect.

Small and relatively flat, the country was ideal territory for German army operations, and Denmark’s small army was significantly smaller than the Werhmacht. Nevertheless, in the early morning hours, a few Danish troops engaged the German army, suffering losses of 16 dead and 20 wounded. The Germans lost 203 soldiers, together with 12 armored cars and several motorcycles and cars destroyed. Four German tanks were damaged. One German bomber was also damaged. Two German soldiers were temporarily captured by the Danes during the brief fighting.

At 04:00 on 9 April 1940, the German ambassador to Denmark— Cecil von Renthe-Fink—called the Danish Foreign Minister Peter Munch and requested a meeting with him. When the two men met 20 minutes later, Renthe-Fink declared that German troops were at that moment moving in to occupy Denmark to protect the country from Franco-British attack. The German ambassador demanded that Danish resistance cease immediately and contact be made between Danish authorities and the German armed forces. If the demands were not met, the Luftwaffe would bomb the capital, Copenhagen.

As the German demands were communicated, the first German advances had already been made, with forces landing by ferry in Gedser at 03:55 and moving north. German Fallschirmjäger units had made unopposed landings and taken two airfields at Aalborg, the Storstrøm Bridge as well as the fortress of Masnedø, the latter being the first recorded attack in the world made by paratroopers.

At 04:20 local time, a reinforced battalion of German infantrymen from the 308th Regiment landed in Copenhagen harbour from the minelayer Hansestadt Danzig, quickly capturing the Danish garrison at the Citadel without encountering resistance. From the harbour, the Germans moved toward Amalienborg Palace to capture the Danish royal family. By the time the invasion forces arrived at the king’s residence, the King’s Royal Guard had been alerted and other reinforcements were on their way to the palace. The first German attack on Amalienborg was repulsed, giving Christian X and his minister’s time to confer with the Danish Army chief General Prior. As the discussions were ongoing, several formations of Heinkel He 111 and Dornier Do 17 bombers roared over the city dropping the OPROP! leaflets.

At 05:25, two squadrons of German Bf 110s attacked Værløse airfield on Zealand and wiped out the Danish Army Air Service by strafing. Despite Danish anti-aircraft fire, the German fighters destroyed ten Danish aircraft and seriously damaged another fourteen, thereby wiping out half of the entire Army Air Service.

Faced with the explicit threat of the Luftwaffe bombing the civilian population of Copenhagen, and only General Prior in favour of continuing to fight, the King Christian X and the entire Danish government capitulated at approximately 06:00 in exchange for retaining political independence in domestic matters.

The invasion of Denmark lasted less than six hours and was the shortest military campaign conducted by the Germans during the war. The rapid Danish capitulation resulted in the uniquely lenient occupation of Denmark, particularly until the summer of 1943, and in postponing the arrest and deportation of Danish Jews until nearly all of them were warned and on their way to refuge in Sweden. In the end, 477 Danish Jews were deported, and 70 of them lost their lives, out of a pre-war total of Jews and half-Jews at a little over 8,000.

Though Denmark had little immediate military significance, it had strategic and to some extent economic importance.

Invasion of Norway

Motivation and order of battle

Norway was important to Germany for two primary reasons: as a base for naval units, including U-boats, to harass Allied shipping in the North Atlantic, and to secure shipments of iron-ore from Sweden through the port of Narvik. The long northern coastline was an excellent place to launch U-boat operations into the North Atlantic in order to attack British commerce. Germany was dependent on iron ore from Sweden and was worried, with justification that the Allies would attempt to disrupt those shipments, 90% of which originated from Narvik.

The invasion of Norway was given to the XXI Army Corps under General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst and consisted of the following main units:

- 69th Infantry Division

- 163rd Infantry Division

- 181st Infantry Division

- 196th Infantry Division

- 214th Infantry Division

- two regiments of the 3rd Mountain Division

The initial invasion force was transported in several groups (Gruppe) by ships of the Kriegsmarine:

- Battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau as distant cover, plus 10 destroyers with 2,000 mountaineering troops under General Eduard Dietl to Narvik;

- Heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and four destroyers with 1,700 troops to Trondheim;

- Light cruisers Köln and Königsberg, artillery training ship Bremse, transport Karl Peters, two torpedo boats and five motor torpedo boats with 1,900 troops to Bergen;

- Light cruiser Karlsruhe, three torpedo boats, seven motor torpedo boats and Schnellboot mothership (Schnellbootbegleitschiff) Tsingtau with 1,100 troops to Kristiansand and Arendal;

- Heavy cruiser Blücher, heavy cruiser (formerly pocket battleship) Lützow, light cruiser Emden, three torpedo boats and eight minesweepers with 2,000 troops to Oslo;

- Four minesweepers with 150 troops to Egersund.

GERMAN INVASION

The German invasion first started on 3 April 1940, when covert supply vessels began to head out in advance of the main force. The Allies initiated their plans on the following day, with sixteen Allied submarines ordered to the Skagerrak and Kattegat to serve as a screen and advance warning for a German response to Operation Wilfred, which was launched the following day when Admiral William Whitworth in HMS Renown set out from Scapa Flow for the Vestfjorden with twelve destroyers.

On 7 April, bad weather began to develop in the region, blanketing the area with a thick fog and causing rough seas making travel difficult. Renown’s force soon got caught in a heavy snowstorm, and HMS Glowworm, one of the destroyer escorts, had to drop out of formation to search for a man swept overboard. The weather aided the Germans, providing a screen for their forces, and in the early morning they sent out Gruppe 1 and Gruppe 2, who had the largest distance to travel.

Though the weather did make reconnaissance difficult, the two German groups were discovered 170 km (105 mi) south of the Naze (the southernmost part of Norway) slightly after 08:00 by Royal Air Force patrols and reported as one cruiser and six destroyers. A trailing squad of bombers sent out to attack the German ships found them 125 km (78 mi) farther north than they had been before. No damage was done during the attack, but the German group’s strength was reassessed as being one battlecruiser, two cruisers and ten destroyers. Because of a strict enforcement of radio silence, the bombers were not able to report this until 17:30.

On learning of the German movement, the Admiralty came to the conclusion that the Germans were attempting to break the blockade that the Allies had placed on Germany and use their fleet to disrupt Atlantic trade routes. Admiral Sir Charles Forbes, Commander-in-Chief of the British Home Fleet, was notified of this and set out to intercept them at 20:15.

With both sides unaware of the magnitude of the situation, they proceeded as planned. Renown arrived at the Vestfjord late that night and maintained position near the entrance while the minelaying destroyers proceeded to their task. Meanwhile, the Germans launched the remainder of their invasion force. The first direct contact between the two sides occurred the next morning without either side’s intention.

British destroyer HMS Glowworm, on its way to rejoin HMS Renown, happened to come up behind German destroyer Z11 Bernd von Arnim and then the Z18 Hans Lüdemann in the heavy fog around 08:00 on 8 April. Immediately a skirmish broke out and the German destroyers fled, signaling for help. The request was soon answered by the pocket battleship Admiral Hipper, which quickly crippled Glowworm. During the action, Glowworm rammed Admiral Hipper. Significant damage was done to Hipper’s starboard, and Glowworm was destroyed by a close range salvo immediately afterwards. During the fight Glowworm had broken radio silence and informed the Admiralty of her situation. She was not able to complete her transmission though, and all the Admiralty knew was that Glowworm had been confronted by a large German ship, shots were fired, and contact with the destroyer could not be re-established. In response, the Admiralty ordered Renown and her single destroyer escort (the other two had gone to friendly ports for fuel) to abandon her post at the Vestfjord and head to Glowworm’s last known location. At 10:45, the remaining eight destroyers of the minelaying force were ordered to join as well.

In the morning of 8 April, the Polish submarine ORP Orzeł confronted and sank the clandestine German troop transport ship Rio de Janeiro off the southern Norwegian port of Lillesand. Amongst the wreckage were discovered uniformed German soldiers and various military supplies. Though Orzeł reported the incident to the Admiralty, they were too concerned by the situation with Glowworm and the presumed German breakout to give it much thought and did not pass the information along. Many of the German soldiers from the wreck were rescued by Norwegian fishing boats and the destroyer Odin. On interrogation the survivors disclosed that they were assigned to protect Bergen from the Allies. This information was passed on to Oslo where the Norwegian Parliament ignored the sinking due to being distracted by the British mining operations off the Norwegian coast.

At 14:00, the Admiralty received word that aerial reconnaissance had located a group of German ships a considerable distance west-northwest of Trondheim, bearing west. This reinforced the notion that the Germans were indeed intending a breakout, and the Home Fleet changed direction from northeast to northwest to again try to intercept. Additionally, Churchill cancelled Plan R 4 and ordered the four cruisers carrying the soldiers and their supplies to disembark their cargo and join the Home Fleet. In actuality, the German ships, Gruppe 2, were only performing delaying circling maneuvers in order to approach their destination of Trondheim at the designated time.

That night, after learning of numerous sightings of German ships south of Norway, Charles Forbes began to doubt the validity of the breakout idea, and he ordered the Home Fleet to head south to the Skagerrak. He also ordered Repulse, along with another cruiser and a few destroyers, to head north and join Renown.

At 23:00, as Forbes was just learning of the incident with Orzeł, Gruppe 5 was confronted by the Norwegian patrol vessel Pol III at the entrance to the Oslofjord. Pol III quickly sent an alarm to the coastal batteries on Rauøy (Rauøy island) and opened fire on the torpedo boat Albatros with her single gun shortly before colliding with it. Albatros and two of her companions responded with anti-aircraft fire, killing the Norwegian captain and setting Pol III on fire. Gruppe 5 continued into the Oslofjord and cleared the outer batteries without incident. Several of the smaller German ships then broke off in order to capture the bypassed fortifications along with Horten.

This activity did not go unnoticed, and soon reports had reached Oslo, leading to a midnight session of the Norwegian cabinet. At this meeting, the cabinet issued orders for the mobilization of four of the six field brigades of the Norwegian Army. The members of the cabinet failed to understand that the partial mobilization they had ordered would, according to the regulations in place, be carried out in secret and without public declarations. Troops would be issued their mobilization orders by post. The only member of the cabinet with in-depth knowledge of the mobilization system, defence minister Birger Ljungberg, failed to explain the procedure to his colleagues. He would later be heavily criticized for this oversight, which led to unnecessary delays in the Norwegian mobilization. Prior to the cabinet meeting, Ljungberg had dismissed repeated demands for a total and immediate mobilization, made by the chief of the general staff, Rasmus Hatledal. Hatledal had approached Ljungberg on 5, 6 and 8 April, asking the defence minister to request the cabinet to issue orders for mobilization. The issue had been discussed in the evening of 8 April, after the Commanding General, Kristian Laake, had joined the calls for a mobilization. At that time the mobilization had been limited to two field battalions in Østfold, further delaying the larger-scale call-up of troops. When Laake’s call for mobilization was finally accepted at some time between 03:30 to 04:00 on 9 April, the Commanding General assumed, like defence minister Ljungberg that the cabinet knew that they were issuing a partial and silent mobilization. The poor communication between the Norwegian armed forces and the civilian authorities caused much confusion in the early days of the German invasion.

At about this time, further north, HMS Renown was heading back to Vestfjord after reaching Glowworm’s last known location and not finding anything. Heavy seas had caused Whitworth to sail more north than normal and had separated him from his destroyers when he encountered the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Renown engaged the two battleships off the Lofoten Archipelago, and during the short battle Renown scored several hits on the German vessels, forcing them to flee north. Renown attempted to pursue, but the German warships used their superior speed to escape.

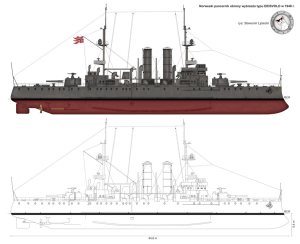

In the Ofotfjord leading to Narvik, the ten German destroyers of Gruppe 1 made their approach. With Renown and her escorts earlier diverted to investigate the Glowworm incident, no British ships stood in their way, and they entered the area unopposed. By the time they had reached the inner area near Narvik, most of the destroyers had peeled off from the main formation to capture the outer batteries of the Ofotfjord, leaving only three to contend with the two old Norwegian coastal defence ships standing guard in Narvik harbour, Eidsvold and Norge. Though antiquated, the two coastal defence ships were quite capable of taking on the much more lightly armed and armoured destroyers. After a quick parlance with the captain of Eidsvold, Odd Isaachsen Willoch, the German ships opened fire pre-emptively on the coastal defence ship, sinking her after hitting her with three torpedoes. Norge entered into the fray shortly after and began to fire on the destroyers, but her marksmen were inexperienced and she did not hit the Germans ships before being sunk by a salvo of torpedoes from the German destroyers.

Following the sinking of Eidsvold and Norge, the commander of Narvik, Konrad Sundlo, surrendered the land forces in the town without a fight.

At Trondheim, Gruppe 2 also faced only minor resistance to their landings. In the Trondheimsfjord, Admiral Hipper engaged the defensive batteries while her destroyers sped past them at 25 knots (46 km/h). A well placed shot by Admiral Hipper severed the power cables for the searchlights and rendered the guns ineffective. Only one destroyer received a hit during the landing.

At Bergen, the defensive fortifications put up stiffer resistance to Gruppe 3‘s approach and the light cruiser Königsberg and the artillery training ship Bremse were damaged, the former seriously. The lack of working lights reduced the effectiveness of the guns though, and the landing ships were able to dock without much opposition. The fortifications were surrendered soon after, when Luftwaffe units arrived.

The fortifications at Kristiansand put up an even more resolute fight, twice repulsing the landing and damaging Karlsruhe, nearly running the cruiser aground. Confusion soon sprung up though when the Norwegians received the order not to fire on British and French ships and the Germans began to use Norwegian codes they had captured at Horten. The Germans used this opportunity to quickly reach the harbour and unload their troops, capturing the town by 11:00.

While most of Gruppe 4 was engaged at Kristiansand, the torpedo boat Greif captured Arendal without any opposition. The main objective at Arendal was the undersea telegraph cable to the United Kingdom.

Gruppe 5 encountered the most serious resistance at the inner defensive fortifications of the Oslofjord, in the vicinity of Drøbak. Blücher, leading the group, approached the forts assuming that they would be taken by surprise and not respond in time, as had been the case with those in the outer fjord. It was not until the cruiser was at point blank range that Oscarsborg Fortress opened fire, connecting with every shot. Within a matter of minutes, Blücher was crippled and burning heavily. The damaged cruiser was sunk by a salvo of antiquated, 40-year-old torpedoes launched from land-based torpedo tubes. She carried much of the administrative personnel intended both for the occupation of Norway and also for the headquarters of the army division assigned to seize Oslo. The cruiser Lützow, also damaged in the attack and believing Blücher had entered a minefield, withdrew with Gruppe 5, 19 km (12 mi) south to Sonsbukten where she unloaded her troops. This distance delayed the arrival of the main German invasion force for Oslo by over 24 hours, though Oslo would still be captured less than 12 hours after the loss of Blücher by troops flown into Fornebu Airfield.

The delay induced by the Norwegian forces gave time for the royal family, Parliament, and with them the national treasury, to flee the capital and continue the fighting against the invasion force.

Fornebu Airfield was originally supposed to be secured by paratroops an hour before the first troops were flown in, but the initial force became lost in the fog and did not arrive. Regardless, the airfield was not heavily defended and the German soldiers who did arrive captured it promptly. The Norwegian Army Air Service’s Jagevingen fighter flight based on Fornebu Airfield resisted with their Gloster Gladiator biplane fighters until ammunition ran out. On 9 April, they had seven serviceable aircraft which managed to shoot down five German aircraft: two Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighters, two Heinkel 111 bombers and one Fallschirmjäger-laden Ju 52 transport. One Gladiator was shot down during the air battle by the future Experte Helmut Lent, while two were strafed and destroyed while refueling and rearming at Fornebu airport. The remaining four operational fighters were ordered to land wherever they could away from the base. The Gladiators landed on frozen lakes around Oslo and were abandoned by their pilots, then wrecked by souvenir-hunting civilians.

The ground personnel of the Fighter Wing soon ran out of ammunition for their anti-aircraft machine guns as well, in the general confusion and focus on readying the fighters for action no one had the presence of mind or the time to issue small-arms ammunition for the personal weapons of the ground personnel. Resistance at Fornebu Airfield came to an end. Norwegian attempts to mount a counter-attack were half-hearted and effectively came to nothing. On learning of this, Oslo itself was declared an open city and soon fully surrendered.

Allied response

Soon after this, the German landings at Trondheim, Bergen, and Stavanger, as well as the skirmishes in the Oslofjord became known to the British. Not willing to disperse too thinly due to the unknown location of the two German battleships, the Home Fleet chose to focus on nearby Bergen and dispatched an attack force. Royal Air Force reconnaissance soon reported stronger opposition than anticipated, and this, along with the possibility that the Germans might be controlling the shore defences, caused them to recall the force and instead use the aircraft carrier HMS Furious to launch torpedo bombers at the enemy ships. The attack never commenced though, as Luftwaffe bombers launched an assault of their own against the Home Fleet first. This attack sank the destroyer HMS Gurkha and then forced the Home Fleet to withdraw north when their anti-aircraft measures proved ineffective. This German air superiority in the area led the British to decide that all southern regions had to be left to submarines and the RAF, while surface vessels would concentrate on the north.

In addition to the German landings in south and central Norway, the Admiralty was also informed via press reports that a single German destroyer was in Narvik. In response to this they ordered the 2nd Destroyer Flotilla, mostly consisting of ships previously serving as escort destroyers for Operation Wilfred, to engage. This flotilla, under the command of Captain Bernard Warburton-Lee, had already detached from the Renown during her pursuit of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, being ordered to guard the entrance to the Vestfjord. At 16:00 on 9 April, the flotilla sent an officer ashore at Tranøy 80 km (50 mi) west of Narvik and learned from the locals that the German force was 4–6 destroyers and a submarine. Warburton-Lee sent these findings back to the Admiralty, concluding with his intention to attack the next day at “dawn, high water”, which would give him the element of surprise and protection against any mines. This decision was approved by the Admiralty in a telegram that night.

Early the following morning, Warburton-Lee led his flagship, HMS Hardy, and four other destroyers into the Ofotfjord. At 04:30, he arrived at Narvik harbour and entered along with HMS Hunter and HMS Havock, leaving HMS Hotspur and HMS Hostile to guard the entrance and watch the shore batteries. The fog and snow were extremely heavy, allowing Warburton-Lee’s force to approach undetected. When they arrived at the harbour itself they found five German destroyers and opened fire, starting the First Battle of Narvik. Warburton-Lee’s ships made three passes on the enemy ships, being joined after the first by Hotspur and Hostile, and sank two of the destroyers, disabled one more, and sank six tankers and supply ships. The German commander, Commodore Friedrich Bonte, lost his life when his flagship Z21 Wilhelm Heidkamp was sunk. Warburton-Lee’s flotilla then left the harbour, almost untouched.

At 06:00, the 2nd Destroyer Flotilla was making their way back to the entrance of the Vestfjord when from the Herjangsfjord behind them three German destroyers emerged, commanded by Commander Erich Bey, and a few minutes later two more arrived in front of them, surrounding Warburton-Lee’s force. Hardy was the first ship to be hit and was quickly taken out of action, beached by one of her officers after she was crippled. Hunter was the next ship put out of commission, coming to a dead halt in the water after several hits. Hotspur was then hit and received damage to her steering system, causing her to crash into Hunter. Several more hits were registered on the pair until Hotspur was able to reverse out of the wreck. Hostile and Havock meanwhile had raced ahead, but turned about and came back to aid the retreat of Hotspur. The German ships having received a few hits and, more importantly, being critically short of fuel, were not able to pursue. As they exited the Ofotfjord, the three British destroyers managed to sink the German supply ship Rauenfels.

Shortly after the First Battle of Narvik, two more German ships were sunk by British forces. During the night of 9/10 April, the submarine HMS Truant intercepted and sank the light cruiser Karlsruhe shortly after it had left Kristiansand. On 10 April, the Fleet Air Arm made a long range attack from their base at Hatston in the Orkney Islands against German warships in Bergen harbour. The attack sank the disabled German light cruiser Königsberg; recorded as the first major warship sunk by aircraft in war.

On 10 April, Furious and the battleship HMS Warspite joined the Home Fleet and another air attack was made against Trondheim in hopes of sinking Admiral Hipper. Admiral Hipper, however, had already managed to escape through the watch set up outside of the port and was on her way back to Germany when the attack was launched; none of the remaining German destroyers or support ships were hit in the assault. Better luck was had in the south when HMS Spearfish severely damaged the heavy cruiser Lützow at midnight on 11 April, putting the German ship out of commission for a year.

With it becoming more evident the German fleet had slipped out of Norwegian waters, Home Fleet continued north to Narvik in the hopes of catching the remaining destroyers. En route the ships suffered further harassment from German bombers, forcing them to divert course west away from the shoreline. By 12 April, they were in range of Narvik and an aerial attack on Narvik from Furious was attempted, but the results were disappointing. It was instead decided to send in the battleship HMS Warspite and a powerful escort force, to be commanded by Whitworth.

On the morning of 13 April, Whitworth’s force entered the Vestfjord using Warspite‘s scouting aircraft to guide the way. Aside from locating two of the German destroyers, the scouting aircraft also sank an enemy submarine, the first such occurrence. Warspite‘s destroyers travelled 5 km (3 mi) in advance of the battleship and were the first to engage their German counterparts which had come to meet them, thus starting the Second Battle of Narvik. Though neither side inflicted notable damage, the German ships were running low on ammunition and were gradually pushed back to the harbour. By that afternoon, most attempted to flee up the Rombaksfjord, the only exception being the Z19 Hermann Künne which beached itself as it made for the Herjangsfjord and was destroyed by HMS Eskimo. Four British destroyers continued to chase the German ships up through the Rombaksfjord, Eskimo soon damaged by the waiting opposition. However, the German situation was hopeless, having run out of fuel and ammunition, and by the time the remaining British ships arrived the German crews had abandoned and scuttled their ships. By 18:30 the British ships were making their way out of the now cleared fjord.

Norwegian situation

The German invasions for the most part achieved their goal of simultaneous assault and caught the Norwegian forces off guard, a situation not aided by the Norwegian government’s order for only a partial mobilization. Not all was lost for the Allies though, as the repulsion of the German Gruppe 5 in the Oslofjord gave a few additional hours of time which the Norwegians used to evacuate the Royal family and the Norwegian Government to Hamar. With the government now fugitive, Vidkun Quisling used the opportunity to take control of a radio broadcasting station and announce a coup, with himself as the new Prime Minister of Norway. Quisling’s coup and his list of new ministers was announced at 19:32. The Quisling coup government remained in place until 15 April, when the Administrative Council was appointed by the Supreme Court of Norway to deal with the civilian administration of the occupied areas of Norway, and Quisling resigned.

In the evening of 9 April, the Norwegian Government moved to Elverum, believing Hamar to be insecure. All German demands were rejected and the Elverum Authorization was passed by the members of the parliament, giving the cabinet wide-ranging powers to make decisions until the next time the Parliament could be assembled under ordinary circumstances. However, the bleakness of the situation prompted them to agree to continued negotiations with the Germans, set for the following day. As a precaution Colonel Otto Ruge, Inspector General of the Norwegian Infantry, set up a roadblock about 110 km (68 mi) north of Oslo, at Midtskogen. The Norwegian position was soon attacked by a small detachment of German troops, led by Eberhard Spiller, the air attaché for the German Embassy, who were racing north in an attempt to capture King Haakon VII. A skirmish broke out and the Germans turned back after Spiller was mortally wounded. On 10 April, the final negotiations between the Norwegians and Germans failed after the Norwegian delegates, led by Haakon VII, refused to accept the German demand for recognition of Quisling’s new government. The same day, panic broke out in German-occupied Oslo, following rumours of incoming British bombers. In what has since been known as “the panic day” the city’s population fled to the surrounding countryside, not returning until late the same evening or the next day. Similar rumours led to mass panic in Egersund and other occupied coastal cities. The origins of the rumours have never been uncovered.

On 11 April, the day after the German-Norwegian negotiations had broken down, 19 German bombers attacked Elverum. The two-hour bombing raid left the town centre in ruins and 41 people dead. The same day 11 Luftwaffe bombers also attacked the town of Nybergsund, in an attempt at killing the Norwegian King, Crown Prince and cabinet.

One of the final acts of the Norwegian authorities before dispersement was the promotion on 10 April of Otto Ruge to the rank of Major General and appointment to Commanding General of the Norwegian Army, responsible for overseeing the resistance to the German invasion. Ruge replaced the 65-year-old General Kristian Laake as Commanding General, the latter having been heavily criticized for what was considered to be passive behaviour during the initial hours of the invasion. Elements in the Norwegian cabinet considered General Laake to be a defeatist. Following the appointment of Ruge the Norwegian attitude became clear, with orders to stop the German advance being issued. With the Germans in control of the largest cities, ports and airfields, as well as most of the arms depots and communication networks, repulsing them outright would be impossible. Ruge instead decided that his only chance lay in playing for time, stalling the Germans until reinforcements from the United Kingdom and France could arrive.

On 11 April, after receiving reinforcements in Oslo, General Falkenhorst’s offensive began; its goal was to link up Germany’s scattered forces before the Norwegians could effectively mobilize or any major Allied intervention could take place. His first task was to secure the Oslofjord area, then to use the 196th and 163rd Infantry Divisions to establish contact with the forces at Trondheim.

Ground campaign

When the nature of the German invasion became apparent to the British military, it began to make preparations for a counter-attack. Dissension amongst the various branches was strong though, as the British Army, after conferring with Otto Ruge, wanted to assault Trondheim in Central Norway while Churchill insisted on reclaiming Narvik. It was decided to send troops to both locations as a compromise. Admiral Lord Cork was in overall command of the Allied operations.

Campaign in Eastern Norway

After the appointment of Ruge as Commanding General on 10 April, the Norwegian strategy was to fight delaying actions against the Germans advancing northwards from Oslo to link up with the invasion forces at Trondheim. The main aim of the Norwegian effort in Eastern Norway was to give the Allies enough time to recapture Trondheim, and start a counter-offensive against the German main force in the Oslo area. The region surrounding the Oslofjord was defended by the 1st Division, commanded by Major General Carl Johan Erichsen. The rest of the region was covered by the 2nd Division, commanded by Major General Jacob Hvinden Haug. Having been prevented from mobilizing in an orderly fashion by the German invasion, improvised Norwegian units were sent into action against the Germans. Several of the units facing the German advance were led by officers especially selected by Ruge to replace commanders who had failed to show sufficient initiative and aggression in the early days of the campaign. The German offensive aimed at linking up their forces in Oslo and Trondheim began on 14 April, with an advance north from Oslo towards the Gudbrandsdalen and Østerdalen valleys. Hønefoss was the first town to fall to the advancing German forces. North of Hønefoss the Germans began meeting Norwegian resistance, first delaying actions and later units fighting organized defensive actions. During intense fighting with heavy casualties on both sides, troops of the Norwegian Infantry Regiment 16 blunted the German advance at the village of Haugsbygd on 15 April. The Germans only broke through the Norwegian lines at Haugsbygd the next day after employing panzers for the first time in Norway. Lacking anti-tank weapons, the Norwegian troops could not hold back the German attack.

The basis for the Norwegian strategy started collapsing already on 13 and 14 April, when the 3,000 troops of the 1st Division in Østfold evacuated across the Swedish border without orders, and was interned by the neutral Swedes. The same day that the 1st Division began crossing into Sweden, the two battalions of Infantry Regiment no. 3 at Heistadmoen Army Camp in Kongsberg capitulated. The 3rd Division, commanded by Major General Einar Liljedahl and tasked with defending Southern Norway, surrendered to the Germans in Setesdal on 15 April, having seen no action up to that point. Some 2,000 soldiers marched into captivity in the Setesdal capitulation. With the abandonment on 20 April of the Franco-British plans for recapturing the central Norwegian city of Trondheim, Ruge’s strategy became practically infeasible.

With the calling off of the Allied plans for recapturing Trondheim, British forces which had been landed at Åndalsnes moved into Eastern Norway. By 20 April three British half-battalions had moved as far south as Fåberg, near the town of Lillehammer. The main British units deployed to Eastern Norway in April 1940 were the Territorials of the 148th Infantry Brigade and the regular 15th Infantry Brigade. In a series of battles with Norwegian and British forces over the next weeks the Germans pushed northwards from Oslo, their main effort through the Gudbrandsdal valley. Particularly heavy fighting took place in places like Tretten, Fåvang, Vinstra, Kvam, Sjoa and Otta. Other German units broke through the Valdres and Østerdalen valleys, in the former case after heavy fighting and an initially successful Norwegian counterattack.

During their advance northwards from Oslo the Germans regularly broke down Norwegian resistance using air strikes. Junkers Ju 87 dive bombers proved particularly effective in demoralizing Norwegian troops opposing the advance. The Norwegian forces’ almost complete lack of anti-aircraft weapons allowed the German aircraft to operate with near impunity. Likewise, when German panzers were employed the Norwegians had no regular countermeasures. The British No. 263 Squadron RAF fighter squadron set up base on the frozen lake Lesjaskogsvatnet on 24 April to challenge German air supremacy, but many of the squadron’s aircraft were destroyed by German bombing on 25 April. The four Gladiators that survived to be evacuated to Setnesmoen army base near Åndalsnes were out of operation by the end of 26 April. Setnesmoen was bombed and knocked out by the Luftwaffe on 29 April.

Norwegian collapse in Southern Norway

After their capture of Kristiansand on 9 April the battalion-strong German invasion force in Southern Norway permitted the evacuation of the civilian population from the city. At the same time the Germans moved to secure the areas surrounding Kristiansand. After several days of confusion and episodes of panic among the Norwegian troops, despite the complete absence of fighting, the 2,000 men of the defending 3rd Division in Setesdal surrendered unconditionally on 15 April.

Campaign in Western Norway

The important western cities of Bergen and Stavanger were captured by the Germans on 9 April. Some 2,000 German soldiers occupied Bergen and captured the Norwegian arms depots there. The small Norwegian infantry forces in Bergen retreated eastwards, blowing up two railway bridges and sections of road after them. Despite the loss of the cities, the regional commander, General William Steffens, ordered a total mobilization. During mid-April the 6,000-strong Norwegian 4th Division, responsible for the defence of Western Norway, was mobilized around the town of Voss in Hordaland. The 4th Division was the only military district outside of Northern Norway to be mobilized completely and in an orderly fashion. The soldiers of the 4th Division managed to repulse the initial German push along the Bergen Line railway line connecting Western and Eastern Norway.

After troops of the more northerly 5th Division had covered the British landings at Åndalsnes, Steffens planned an offensive aimed at recapturing Bergen. To achieve this aim the 4th Division had a total mobilized force of 6,361 soldiers and 554 horses. General Steffens’ plans were made redundant when General Ruge on 16 April ordered most of the division’s forces to be redeployed to Valdres and Hallingdal, in order to reinforce the main front in Eastern Norway. The focus of the remaining forces in Western Norway became to prevent the Germans from advancing from the areas around Bergen. Norwegian naval forces, organized into three regional commands by Admiral Tank-Nielsen, prevented German intrusions into Hardangerfjord and Sognefjord. In total the Royal Norwegian Navy fielded some 17–18 warships and five to six aircraft in Western Norway following the German capture of Bergen. After the Luftwaffe bombed and severely damaged Voss and the surrounding countryside on 23–25 April, inflicting civilian casualties, the Germans captured the town on 26 April.

Following the fall of Voss, General Steffens evacuated the remains of his forces northward, evacuating the south side of the Sognefjord on 28 May (except for a small contingent at Lærdal). He set up his own headquarters at Førde and prepared for the further defence of Sogn og Fjordane. On 30 April a message from General Otto Ruge was communicated, telling of the evacuation of all allied troops and also of the King and Army command, from southern Norway. With no help forthcoming from either allied or Norwegian forces, on 1 May 1940, Steffens ordered his troops to disband. The advancing German forces were informed of the whereabouts of the Norwegian troops, and agreed to let them disband unmolested. On the night between 1 May and 2 May, Steffens left for Tromsø with three naval aircraft, effectively ending the campaign in the region. No allied land troops had been involved in the fighting in Hordaland and Sogn og Fjordane. Another two aircraft flew to the United Kingdom to undergo service. Although the Royal Norwegian Navy’s ships in Western Norway were ordered to evacuate to the United Kingdom or Northern Norway, only the auxiliary Bjerk sailed to the United Kingdom and Steinar to Northern Norway. The remaining ships were either prevented from leaving due to massive desertions, or had commanders who chose to disband their men rather than risk the voyages to Allied-controlled territory. The last Norwegian forces in Western Norway only disbanded in Florø on 18 May 1940.

Campaign in Central Norway

The original plans for the campaign in Central Norway called for a three pronged attack against Trondheim by Allied forces while the Norwegians contained the German forces to the south. It was called Operation Hammer, and would land Allied troops at Namsos to the north (Mauriceforce), Åndalsnes to the south (Sickleforce), and around Trondheim itself (Hammerforce). This plan was quickly changed though, as it was felt that a direct assault on Trondheim would be far too risky and therefore only the northern and southern forces would be used.

In order to block the expected allied landings the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht ordered a Fallschirmjäger company to make a combat drop on the railway junction of Dombås in the north of the Gudbrandsdal valley. The force landed on 14 April and managed to block the rail and road network in Central Norway for five days before being forced to surrender to the Norwegian Army on 19 April.

A British vanguard force arrived at Åndalsnes on 12 April. The main landing of Sickleforce, consisting primarily of the British 148th Infantry Brigade and commanded by Major General Bernard Paget, occurred on 17 April. The successful Norwegian mobilization in the area opened the opportunity for the British landings.

In the waning hours of 14 April, Mauriceforce, composed primarily of the British 146th Infantry Brigade and commanded by Major General Adrian Carton de Wiart made their initial landings at the Norwegian port town of Namsos. During the trip the force had been transferred to destroyers instead of bulky transport ships due to the narrow waters of the fjord leading to Namsos; in the confusion of the transfer a great deal of their supplies and even the brigade commander were misplaced.

Another great problem for Mauriceforce was the lack of air support and effective anti-aircraft defences, something of which the Luftwaffe took full advantage. On 17 April the force moved forward from Namsos to positions around the village of Follafoss and the town of Steinkjer. French troops arrived at Namsos late on 19 April. On 20 April German aircraft bombed Namsos, destroying most of the houses in the town centre, and large portions of the supply storage for allied troops, leaving de Wiart without a base. Regardless, he moved 130 km (81 mi) inland to Steinkjer and linked up with the Norwegian 5th Division. Constant aerial harassment prevented any kind of offensive from taking place though, and on 21 April Mauriceforce was attacked by the German 181st Division from Trondheim. De Wiart was forced to fall back from these assaults, leaving Steinkjer for the Germans. On 21 and 22 April Steinkjer was bombed by the Luftwaffe, leaving four-fifths of the town in ruins and more than 2,000 people homeless. By 24 April Steinkjer and the surrounding areas had been occupied by the Germans.

The end of the campaign in Central and South Norway

By 28 April, with both groups checked by the Germans, the Allied leadership decided to withdraw all British and French forces from the southern and central regions of Norway. The Allied retreat was covered by Norwegian forces, which were then demobilized to avoid having the soldiers taken prisoner by the Germans. On 30 April the Germans advancing from Oslo and Trondheim linked up.

On 28 and 29 April the undefended port town of Kristiansund had been heavily bombed by the Luftwaffe, as was the nearby port of Molde, which functioned as the headquarters of the Norwegian government and King. The town of Ålesund had also suffered heavily from German bombing during the last days of April.

Sickleforce managed to return to Åndalsnes and escape by 2 May at 02:00, only a few hours before the German 196th Division captured the port. The western Norwegian port had been subjected to heavy German bombing between 23 and 26 April, and had been burning until 27 April. The village of Veblungsnes and the area around Åndalsnes train station suffered particularly heavy damage. By the time the Germans arrived, some 80% of Åndalsnes lay in ruins. Mauriceforce, their convoys delayed by thick fog, were evacuated from Namsos on 2 May, though two of their rescue ships, the French destroyer Bison and the British destroyer Afridi were sunk by Junkers Ju 87 dive bombers.

Organized Norwegian military resistance in the central and southern parts of Norway ceased on 5 May, with the capitulation of the forces fighting at Hegra in Sør-Trøndelag and at Vinjesvingen in Telemark.

The failure of the central campaign is considered one of the direct causes of the Norway Debate, which resulted in the resignation of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and the appointment of Winston Churchill to the office.

Having evacuated from Molde during German air attacks on 29 April, King Haakon VII and his government arrived in Tromsø in Northern Norway by 1 May. For the remaining weeks of the Norwegian Campaign Tromsø was the de facto capital of Norway, as the headquarters of the King and cabinet.

Campaign in Northern Norway

In Northern Norway the Norwegian 6th division, commanded by General Carl Gustav Fleischer faced the German invasion forces at Narvik. Following the German invasion General Fleischer assumed the position as commander-in-chief of all Norwegian forces in Northern Norway. The Norwegian counter-offensive against the Germans at Narvik was hampered by Fleischer’s decision to retain significant forces in Eastern Finnmark to guard against a possible Soviet attack in the far north.

Along with the Allied landings at Åndalsnes and Namsos, aimed against Trondheim, further forces were deployed to the north of Norway. These forces were tasked with the objective of recapturing Narvik. Like the campaign in the south, the Narvik expedition also faced numerous obstacles.

One of the first problems faced by the Allies was the fact that the command was not unified, or even truly organized. Naval forces in the area were led by Admiral of the Fleet William Boyle, 12th Earl of Cork who had been ordered to rid the area of the Germans as soon as possible. In contrast, the commander of the ground forces, Major General Pierse Mackesy, was ordered not to land his forces in any area strongly held by the Germans and to avoid damaging populated areas. The two met on 15 April to determine the best course of action. Boyle argued for an immediate assault on Narvik and Mackesy countered that such a move would lead to the decimation of his attacking troops. Boyle eventually conceded to Mackesy’s viewpoint.

Mackesy’s force was originally codenamed Avonforce, later Rupertforce. The force consisted of the 24th Guards Brigade, as well as French and Polish units led by Brigadier Antoine Béthouart. The main force began landing at Harstad, a port town on the island of Hinnøya, on 14 April. The first German air attacks on Harstad began on 16 April, but anti-aircraft defences prevented serious damage. Only in late May did the Germans succeed in causing destruction in Harstad; a raid on 20 May destroying oil tanks and civilian houses and another raid on 23 May hitting Allied shipping in the harbour.

On 15 April, the Allies scored a significant victory when the Royal Navy destroyers Brazen and Fearless, which were escorting the troop-carrying Convoy NP1, managed to force the German U-boat U-49 to surface and scuttle in the Vågsfjorden. Found floating around the sinking U-boat were documents detailing the dispositions, codes and operational orders of all U-boats in the Norwegian operational area, providing the Allies with an efficient and valuable tool when planning troop and supply convoys to the campaign in Northern Norway.

After the Allied failure in Central Norway, more preparation was given to the northern forces. Air cover was provided by two squadrons of carrier-transported fighters operating from Bardufoss Air Station, the re-equipped No. 263 Squadron RAF with Gloster Gladiators and No. 46 Squadron RAF with Hawker Hurricanes.

As part of the Allied counter-offensive in Northern Norway, French forces made an amphibious landing at Bjerkvik on 13 May. The naval gunfire from supporting Allied warships destroyed most of the village and killed 14 civilians before the Germans were dislodged from Bjerkvik.

On 28 May, two French and one Norwegian battalion attacked and recaptured Narvik from the Germans. To the south of the city Polish troops advanced eastwards along the Beisfjord. Other Norwegian troops were pushing the Germans back towards the Swedish border near Bjørnfjell. On 25 May, three days before the recapture of Narvik, the Allied commanders had received orders to evacuate from Norway. The attack on the city was in part carried out to mask from the Germans the Allies’ intention of leaving Norway. Among those who argued against evacuating Norway was Winston Churchill, who later expressed that the decision had been a mistake. Shortly after the 28 May Allied recapture of Narvik, the city was bombed and heavily damaged by the Luftwaffe.

While the Norwegian and Allied forces were advancing at Narvik, German forces were moving swiftly northwards through Nordland to relieve Dietl’s besieged troops. The captured Værnes Air Station near Trondheim was rapidly expanded and improved to provide the Luftwaffe with a base from which to support the Narvik sector. As the German forces moved northwards, they also gained control of the basic facilities at Hattfjelldal Airfield in Hattfjelldal to support their bomber operations. In the evening of 27 May the port city of Bodø was bombed and strafed by the Luftwaffe. The bombing raid destroyed the local airport, radio station and 420 of the town’s 760 buildings, killing 15 people and leaving a further 5,000 homeless in the process. Bodø was captured by the advancing German units on 1 June, and the British-operated improvised air strip which had been hit during the 27 May air raid fell into German hands. The air strip at Bodø provided the Germans with an air base much closer to the Narvik fighting, and was of great significance for their continued advance northwards.

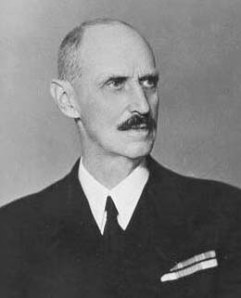

Operation Alphabet, the general Allied retreat from Norway, had been approved on 24 May. The Norwegian authorities were only informed of the decision on 1 June. After a meeting on 7 June where the decision to carry on the fight abroad was made, King Haakon VII, Crown Prince Olav and the Norwegian cabinet left Norway on the British cruiser Devonshire and went into exile in the United Kingdom. Without supplies from the Allies the Norwegian Army would soon have been unable to continue the fight. Both the King and the Crown Prince had considered the possibility of remaining in Norway, but had been persuaded by the British diplomat Cecil Dormer to instead follow the government into exile. The Crown Prince suggested that he should remain and assist the Administrative Council in easing the effects of the occupation, but due to the King’s old age it was decided that they both had to go into exile, in order to avoid complications should the King die while abroad. By 8 June, after destroying rail lines and port facilities, all Allied troops had been evacuated. The Germans had launched Operation Juno to relieve pressure on the Narvik garrison and, after discovering the evacuation, shifted the mission to a hunt and sunk two British destroyers and the aircraft carrier Glorious. Before the British warships were sunk, however, the destroyer Acasta torpedoed and damaged Scharnhorst. Shortly after the encounter the British submarine HMS Clyde intercepted the German ships and torpedoed Gneisenau, causing severe damage.

The Norwegian forces on the mainland capitulated to the Germans on 10 June 1940. Units fighting on the front had been ordered to disengage in the early hours of 8 June. Fighting ceased at 24:00 on 9 June. The formal capitulation agreement for forces fighting in mainland Norway was signed at the Bristol Hotel in Trondheim at 17:00 on 10 June 1940. Lieutenant Colonel Ragnvald Roscher Nielsen signed for the Norwegian forces, Colonel Erich Buschenhagen for the German side. A capitulation agreement for the Norwegian forces fighting at Narvik was also signed the same day, at Bjørnfjell. The signatories of this agreement, the last local capitulation of Norwegian troops during the campaign, were General Eduard Dietl for the Germans, and Lieutenant Colonel Harald Wrede Holm for the Norwegians. The 62-day campaign made Norway the country to withstand a German invasion for the longest period of time, aside from the Soviet Union.

Occupation

With the capitulation of Norway’s mainland army a German occupation of the country began. Although the regular Norwegian armed forces in mainland Norway laid down their arms in June 1940, there was a fairly prominent resistance movement, which proved increasingly efficient during the later years of occupation. The resistance to the German occupation began in the autumn of 1940, steadily gaining strength and becoming better organized. Despite the Gestapo infiltrating and destroying many of the early organizations, the resistance movement survived and grew. The last year of the war saw an increase in sabotage actions by the exile government-aligned Norwegian resistance organization Milorg, although the organization’s main goal was to retain intact guerilla forces to aid an Allied invasion of Norway. In addition to Milorg, many independent, mostly communist, resistance groups operated in occupied Norway, attacking German targets without coordinating with the exiled Norwegian authorities.