The 1914 Christmas Truce.

Music hall

In 1914, music hall was by far the most popular form of popular song. It was listened to and sung along to in theatres which were getting ever larger (three thousand seaters were not uncommon) and in which the musical acts were gradually overshadowing all other acts (animal imitators, acrobats, human freaks, conjurors, etc.) The industry was more and more dominated by chains of theatres like Moss, and by music publishers, since selling sheet music was very profitable indeed—a real hit could sell over a million copies.

The seats at the music hall could be very cheap and attracted a largely working class audience, for whom a gramophone would generally be too expensive. Although many ordinary people had heard gramophones in seaside resorts or in park concerts organized by local councils, many more would discover the gramophone while in the army, since gramophone manufacturers produced large numbers of portable gramophones “for our soldiers in France”.

The repertoire of songs was dominated by the jauntily comic. The domineering wife or mother-in-law, the bourgeois, the foreigner, the Black man and the Jew were cheerfully mocked in an atmosphere where objections to sexism or racism in songs were practically unknown. Many more songs were made up of tongue-twisters or other comic elements. Sentimental love songs and dreams of an ideal land (Ireland or Dixie in particular) made up another major category. Practically all the songs of the era are unknown today; several thousand music hall songs were published in the UK alone during the war years.

The singers moved from town to town, many just scraping together a living, but a few making a lot of money. The key stars at the time included Marie Lloyd, Vesta Tilley, George Formby, Sr., Harry Lauder, Gertie Gitana and Harry Champion.

Enthusiasm for the war

At the outbreak of war, many songs were produced which called for young men to join up. Examples included “We Don’t Want to Lose You, but We Think You Ought to Go”, “Now You’ve Got the Khaki On” or “Kitcheners’ Boys”. After a few months of war and rising numbers of deaths, the recruitment songs all but disappeared, and the 1915 “Greatest hits” collection published by Francis and Day contains no recruitment songs at all. The music hall songs which mentioned the war (about a third of the total produced) were more and more dreams about the end of the war—”When the Boys Come Home” and “Keep the Home Fires Burning” are two well-known examples.

Popular, patriotic songs that were composed during the war also served to raise the morale of soldiers and civilians alike. These hit songs covered a variety of themes, such as separation of loved ones, boot camp, war as an adventure, and humorous songs about the military life.

Because there were no radios or televisions that reported the conditions of the battlefields, Americans had a romantic view of war. Not only were many of the songs patriotic, but they were also romantic. These songs portrayed soldiers as brave and noble, while the women were portrayed as fragile and loyal as they waited for their loved ones.

It’s a Long Way to Tipperary

“It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” is a British music hall song written by Jack Judge and co-credited to, but not co-written by, Henry James “Harry” Williams. It was allegedly written for a 5-shilling bet in Stalybridge on 30 January 1912 and performed the next night at the local music hall. Now commonly called “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”, the original printed music calls it “It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary.” It became popular among soldiers in the First World War and is remembered as a song of that war.

Welcoming signs in the referenced town of Tipperary, Ireland, humorously declare, “You’ve come a long way…” in reference to the song.

Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit-Bag

“Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit-Bag, and Smile, Smile, Smile” is the full name of a World War I marching song, published in 1915 in London. It was written by Welsh songwriters, George Henry Powell under the pseudonym of “George Asaf”, and set to music by his brother Felix Powell.

It was featured in the American show Her Soldier Boy, which opened in December 1916.

Performers associated with this song include Edward Hamilton, the Victor Military Band, James F. Harrison, Murray Johnson, Reginald Werrenrath, and the Knickerbocker Quartet.

A later play presented by the National Theatre recounts how these music hall stars rescued the song from their rejects pile and re-scored it to win a wartime competition for a marching song. It became very popular, boosting British morale despite the horrors of that war. It was one of a large number of music hall songs aimed at maintaining morale, recruiting for the forces, or defending Britain’s war aims.

Keep the Home-Fires Burning (‘Till the Boys Come Home)

Is a British patriotic First World War song composed in 1914 by Ivor Novello with words by Lena Guilbert Ford (whose middle name was sometimes printed as “Gilbert”).

The song was published first as ‘Till the Boys Come Home on 8 October 1914 by Ascherberg, Hopwood and Crew Ltd. in London. A new edition was printed in 1915 with the name Keep the Home-Fires Burning. The song became very popular in the United Kingdom during the war, along with It’s a Long Way to Tipperary.

James F. Harrison recorded Keep the Home-Fires Burning in 1915, as did Stanley Kirkby in 1916. Another popular recording was sung by tenor John McCormack in 1917, who was also the first to record It’s a Long Way to Tipperary in 1914. (See External links below to hear these recordings of Keep the Home-Fires Burning.) Other versions include one by Frederick J. Wheeler and one by the duet Reed Miller & Frederick Wheeler.

There is a misconception that Ivor Novello’s mother wrote the lyrics for the song (propagated—for example—by patter in recorded performances of British musical comedy duo Hinge and Bracket) but Lena Ford (an American) was a friend and collaborator of Novello, not a blood relation.

“There’s a Long, Long Trail”

Is a popular song of World War I. The lyrics were by Stoddard King (1889–1933) and the music by Alonzo “Zo” Elliott, both seniors at Yale. It was published in London in 1914, but a December, 1913 copyright for the music is claimed by Zo Elliott.

In Elliott’s own words to Marc Drogin shortly before his death in 1964, he created the music as an idle pursuit one day in his dorm room at Yale in 1913. King walked in, liked the music and suggested a first line. Elliott sang out the second, and so they went through the lyrics. And they performed it—with trepidation—before the fraternity that evening. The interview was published as an article in the New Haven Register and later reprinted in Yankee Magazine. It then appeared on page 103 of “The Best of Yankee Magazine” [ISBN 0-89909-079-6] In the interview, he recalled the day and the odd circumstances that led to the creation of this historic song.

Roses of Picardy

“Roses of Picardy” is a British popular song with lyrics by Frederick Weatherly and music by Haydn Wood. Published in London in 1916 by Chappell & Co, it was one of the most famous songs of the First World War and has been recorded frequently up to the present day.

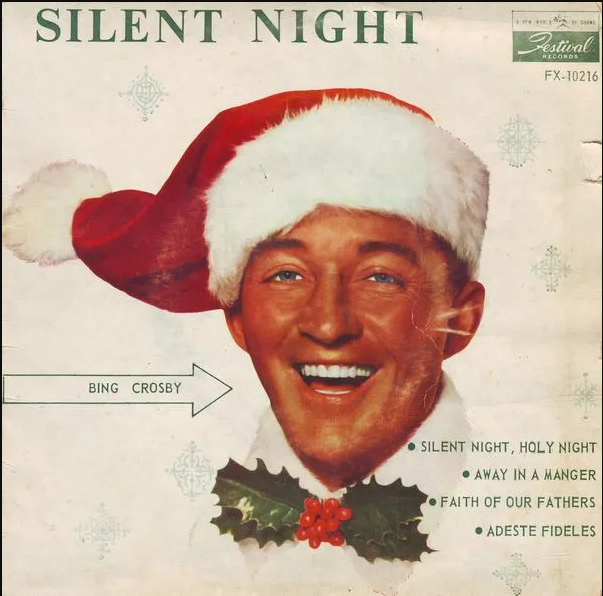

“Silent Night”

(German: Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht) is a popular Christmas carol, composed in 1818 by Franz Xaver Gruber to lyrics by Joseph Mohr in the small town of Oberndorf bei Salzburg, Austria. It was declared an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO in 2011. The song has been recorded by a large number of singers from every music genre. There is a version sung by Bing Crosby that is the third best-selling single of all-time.

One day peace will prevail.

See also:

Interview with Carlos Palop, CEO, UniteSync –link here