By 1914, trenches were a common aspect of warfare, reflecting the straightforward need for soldiers on the frontline to protect themselves against enemy fire. Standard military manuals provided instructions for digging trenches, and armies had equipment for doing so. But there was no precedent for the scale and duration of the trench warfare that was such a feature of World War I

By the end of 1915, there was a more or less continuous line of trenches stretching 740 km (460 miles) across Europe, from the Belgian coast to Switzerland, and a somewhat less continuous line in the East extending for 1.300 km (800 miles) from the Baltic to the Carpathians. All the order fronts in the war – in Northern Italy, Gallipoli in Turkey, Palestine and the Caucuses – had their own trench systems. At first, trenches were considered to be a temporary, necessary measure. Eventually, some of them became home for thousands of troops for years.

The essentials of ant trench were simple. It had to be deep enough for a man to stand. Without his head presenting a target for enemy snipers. It also had to be narrow, so that it was not an easy target for an enemy shell or mortar. It was advantageous if it wasn’t straight. Frequent ‘kinks’, which the British called ‘traverses’, stopped blast shrapnel or fore sweeping the entire length of the trench. It needed a firestep, a raised platform, in its front wall, so that soldiers could, step up to shoot over the top if the enemy attacked.

Where the ground was sodden, as it regularly was in parts of Flanders in Belgium, trenches had to be shallow to avoid flooding, with a parapet of earth and sandbags built up in front. Where the ground was dry and firm, as at the Somme, trenches could be provided with deep underground bunkers to protect troops against shellfire. In some places, however, defences never progressed beyond a single trench fronted by a few strands of barbed wire.

Trench systems of considerable complexity developed over time. Saps (short trenches) were dug forwards into no-man’s land between the opening trenches. Parallel lines of support and reserve trenches were dug behind the front line, and maze of communication trenches linked the front line to the rear. On the Western Front, the Germans eventually constructed complex defensive systems 15 km (9 miles) across, with a series of trenches, disguised as machine-gun emplacements, and cunningly sited strongpoints that were reinforced with concrete fortifications.

Conditions on the front varied, French trenches provided notoriously poor living conditions. The Germans, by contrast, built dry and warm concrete bunkers and even installed electric lighting in some trench systems. Life in the trenches could range from tolerable to almost unbearable. On a quiet sector of the front, daily routines might carry a man through months of the war with only limited danger. Enemies separated by no more than 100-200m (100-200 yd) of no Man’s land adopted a system of live-and-let-live as the path to mutual survival. A day typically began with ‘Stand to’ at dawn. Often the occasion for a ritualistic exchange of fire expected to hurt no one. Then rations were brought up from the rear. Tasks such as cleaning weapons and maintaining or extending trenches filled the day until “Stand Down” at dusk. Night was a time for repairing barbed wire or moving troops and equipment.

On an active front, Commanders insisted on constant harassment of the enemy. Front line units suffered a grinding attrition of casualties from sniper fire, mortars or artillery. At night patrols were sent out into no man’s land or raids were mounted against heavy trenches, producing heavy casualties for both sides. Few soldiers went “Over the Top” in a major offensive more than once. Or twice. When they did, it was an experience they would never forget. Observation of the enemy, either through periscopes or at advanced listening posts thrust forward into No Man’s Land, it was a 24-hour-a-day task, and any soldier who fell asleep on sentry duty was severely punished. Soldiers on the Western Front Would typically spend less than a week on the front line, before being rotated o the reserve line of the rear. Where they labored on exhausting tasks such as carrying ammunition to the front line.

Infestation with lice was almost universal in the trenches, which also swarmed with well-fed rats. Sometimes corpses and body parts became embedded in trench walls, as it was often too dangerous to retrieve them. Latrine facilities could be primitive. On The Western Front, troops were usually adequately clothed and fed, but such was not the case on other fronts. Extreme weather could turn the trench experience into a nightmare. In the summer heat at Gallipoli, troops were tortured by thirst and racked by disease, In Flanders, heavy rain flooded trenches, turning the battle area into a quagmire; troops standing for days in deep water suffered “trench foot” which could lead to gangrene and amputation.

The intensity of World War I trench warfare meant about 10% of the fighting soldiers were killed. This compared to 5% killed during the Second Boer War and 4.5% killed during World War II. For British and Dominion troops serving on the Western Front, the proportion of troops killed was 12.5%, while the total proportion of troops who became casualties (killed or wounded) was 56%.

Medical services were primitive and antibiotics had not yet been discovered. Relatively minor injuries could prove fatal through onset of infection and gangrene. The Germans recorded that 15% of leg wounds and 25% of arm wounds resulted in death, mainly through infection. The Americans recorded 44% of casualties who developed gangrene died. Fifty percent of those wounded in the head died and 99% of those wounded in the abdomen died, Seventy five percent of wounds came from shell fire. A wound resulting from a shell fragment was usually more traumatic than a gunshot wound.

A shell fragment would often introduce debris, making it more likely that the wound would become infected. These factors meant a soldier was three times more likely to die from a shell wound to the chest than from a gunshot wound. The blast from shell explosions could also kill by concussion. In addition to the physical effects of shell fire, there was the psychological damage. Men who had to endure prolonged bombardment would often suffer debilitating shell shock, a condition not well understood at the time.

As in many other wars, World War I’s greatest killer was disease. Sanitary conditions in the trenches were quite poor, and common infections included dysentery, typhus, and cholera. Many soldiers suffered from parasites and related infections. Poor hygiene also led to fungal conditions, such as trench mouth and trench foot. Another common killer was exposure, since the temperature within a trench in the winter could easily fall below freezing. Burial of the dead was usually a luxury that neither side could easily afford. The bodies would lie in no man’s land until the front line moved, by which time the bodies were often unidentifiable. On some battlefields, such as at the Nek in Gallipoli, the bodies were not buried until after the war. On the Western Front, bodies continue to be found as fields are ploughed and building foundations dug.

At various times during the war—particularly early on—official truces were organised so that the wounded could be recovered from no man’s land and the dead could be buried. Generally, senior commands disapproved of any slackening of the offensive for humanitarian reasons and so ordered their troops not to permit enemy stretcher-bearers to operate in no man’s land. However, this order was almost invariably ignored by the soldiers in the trenches, who knew that it was to the mutual benefit of the fighting men of both sides to allow the wounded to be retrieved. So, as soon as hostilities ceased, parties of stretcher bearers, marked with Red Cross flags, would go out to recover the wounded, sometimes swapping enemy wounded for their own.

There were occasions when this unofficial cease fire was exploited to conduct a reconnaissance or to reinforce or relieve a garrison. One famous truce was the Christmas truce between British and German soldiers in the winter of 1914 on the front near Armentieres. German soldiers began singing Christmas carols and soon soldiers left their trenches. The soldiers exchanged gifts and stories, and played several games of football. The commanders of the warring nations disapproved of this cease fire, and the British court-martialed several of their soldiers.

The common infantry soldier had only a few weapons to use in the trenches: the rifle, bayonet, and hand grenade. Over time, and given experience, more effective and deadly weapons were developed.

A specialised group of fighters called trench sweepers (Nettoyeurs de Tranchées or Zigouilleurs) evolved to fight within the trenches. They cleared surviving enemy personnel from recently overrun trenches and made clandestine raids into enemy trenches to gather intelligence.

Volunteers for this dangerous work were often exempted from participation in frontal assaults over open ground and from routine work like filling sandbags, draining trenches, and repairing barbed wire in no-man’s land. When allowed to choose their own weapons, many selected grenades, knives and pistols. FN M1900 pistols were highly regarded for this work, but never available in adequate quantities. Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless, Savage Model 1907, Star Bonifacio Echeverria and Ruby pistols were widely used.

According to the semi-biographical war novel All Quiet on the Western Front, many soldiers preferred to use a sharpened spade as an improvised melee weapon instead of the bayonet, as the bayonet tended to get “stuck” in stabbed opponents, rendering it useless in heated battle. The shorter length also made them easier to use in the confined quarters of the trenches. These tools could then be used to dig in after they had taken a trench. Since the troops were often not adequately equipped for trench warfare, improvised weapons were common in the first encounters, such as short wooden clubs and metal maces, as well as trench knives and brass knuckles. As the war progressed, better equipment was issued, and improvised arms were discarded.

Used by American soldiers in the Western front, the pump action shotgun was a formidable weapon in short range combat, enough so that Germany lodged a formal protest against their use on 14 September 1918, stating “every prisoner found to have in his possession such guns or ammunition belonging thereto forfeits his life”, though this threat was apparently never carried out. The U.S. military began to issue models specially modified for combat, called “trench guns”, with shorter barrels, higher capacity magazines, no choke, and often heat shields around the barrel, as well as lugs for the M1917 bayonet. Anzac and some British soldiers were also known to use sawn-off shotguns in trench raids, because of their portability, effectiveness at close range, and ease of use in the confines of a trench. This practice was not officially sanctioned, and the shotguns used were invariably modified sporting guns.

The hand grenade came to be one of the primary infantry weapons of trench warfare. Both sides were quick to raise specialist grenadier groups. The grenade enabled a soldier to engage the enemy without exposing himself to fire, and it did not require precise accuracy to kill or maim. Another benefit was that if a soldier could get close enough to the trenches, enemies hiding in trenches could be attacked. The Germans and Turks were well equipped with grenades from the start of the war, but the British, who had ceased using grenadiers in the 1870s and did not anticipate a siege war, entered the conflict with virtually none, so soldiers had to improvise bombs with whatever was available (see Jam Tin Grenade). By late 1915, the British Mills bomb had entered wide circulation, and by the end of the war 75 million had been used.

Various mechanical devices were invented for throwing hand grenades into enemy trenches. The Germans used the Wurfmaschine, a spring-powered device for throwing a hand grenade about 200 m (220 yd). The French responded with the Sauterelle and the British with the Leach Trench Catapult and West Spring Gun which had varying degrees of success and accuracy. By 1916, catapult weapons were largely replaced by rifle grenades and mortars.

Tanks were first introduced by the British as a means to break the stalemate of trench warfare. They were first deployed at the Battle of the Somme in limited numbers. They proved unreliable and ineffective at first, largely because of poor strategic and tactical planning, being spread too thinly on the ground. In addition, they were originally used over ground torn apart by large amounts of shell fire, which early tanks had trouble traversing. Later on, improved tanks and tactics allowed them to break through enemy lines to become a significant element of warfare. However, their impact was less than it could have potentially been, given their late introduction into the war and the inherent issues that plagued the primitive machines.

The Germans embraced the machine gun from the outset—in 1904, sixteen units were equipped with ‘Maschinengewehr’—and the machine gun crews were the elite infantry units; these units were attached to Jaeger (light infantry) battalions. By 1914, British infantry units were armed with two Vickers machine guns per battalion, the Germans had six per battalion, the Russians eight. It would not be until 1917 that every infantry unit of the American forces carried at least one machine gun. After 1915, the Maschinengewehr 08 was the standard issue German machine gun; its number “08/15″ entered the German language as idiomatic for “dead plain”. At Gallipoli and in Palestine the Turks provided the infantry, but it was usually Germans who manned the machine guns.

The British High Command were less enthusiastic about machine guns, supposedly considering the weapon too “unsporting” and encouraging defensive fighting; and they lagged behind the Germans in adopting it. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig is quoted as saying in 1915, “The machine gun is a much overrated weapon; two per battalion is more than sufficient”. The defensive firepower of the machinegun was exemplified during the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 60,000 British soldiers were rendered casualties “the great majority lost under withering machine gun fire”.

In 1915 the Machine Gun Corps was formed to train and provide sufficient heavy machine gun teams.

It was the Canadians that made the best practice, pioneering area denial and indirect fire (soon adopted by all Allied armies) under the guidance of former French Army Reserve officer Major General Raymond Brutinel. Minutes before the attack on Vimy Ridge the Canadians thickened the artillery barrage by aiming machine guns indirectly to deliver plunging fire on the Germans. They also significantly increased the number of machine guns per battalion. To match demand, production of the Vickers machine gun was contracted to firms in the United States. By 1917, every company in the British forces were also equipped with four Lewis light machine guns, which significantly enhanced their firepower.

The heavy machine gun was a specialist weapon, and in a static trench system was employed in a scientific manner, with carefully calculated fields of fire, so that at a moment’s notice an accurate burst could be fired at the enemy’s parapet or a break in the wire. Equally it could be used as light artillery in bombarding distant trenches. Heavy machine guns required teams of up to eight men to move them, maintain them, and keep them supplied with ammunition. This made them impractical for offensive manoeuvres, contributing to the stalemate on the Western Front

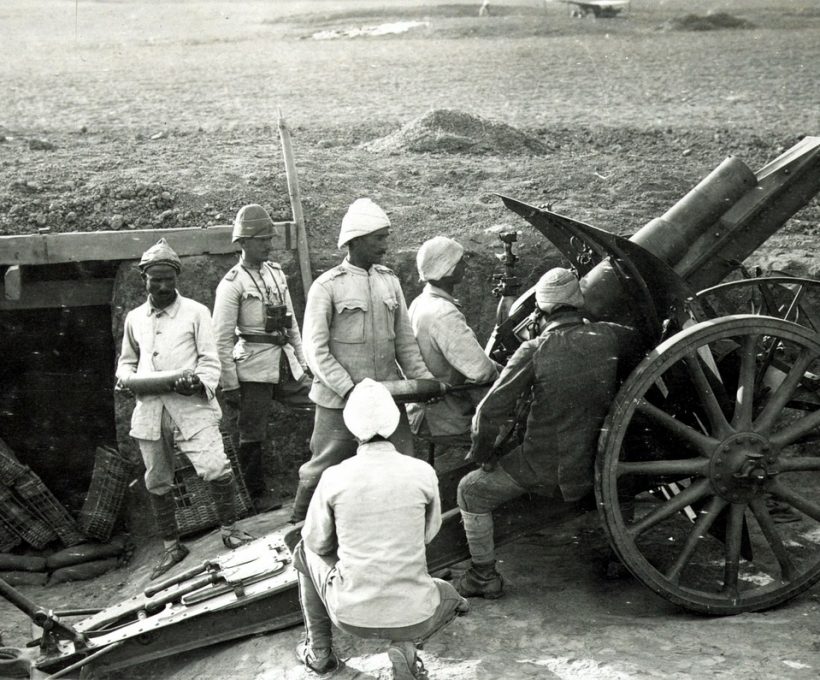

Mortars, which lobbed a shell in a high arc over a relatively short distance, were widely used in trench fighting for harassing the forward trenches, for cutting wire in preparation for a raid or attack, and for destroying dugouts, saps and other entrenchments. In 1914, the British fired a total of 545 mortar shells; in 1916, they fired over 6,500,000. Similarly, howitzers, which fire on a more direct arc than mortars, raised in number from over 1,000 shells in 1914, to over 4,500,000 in 1916. The smaller numerical difference in mortar rounds, as opposed to howitzer rounds, is presumed by many to be related to the expanded costs of manufacturing the larger and more resource intensive howitzer rounds.

The main British mortar was the Stokes, a precursor of the modern mortar. It was a light mortar, simple in operation, and capable of a rapid rate of fire by virtue of the propellant cartridge being attached to the base shell. To fire the Stokes mortar, the round was simply dropped into the tube, where the percussion cartridge was detonated when it impacted the firing pin at the bottom of the barrel, thus being launched. The Germans used a range of mortars. The smallest were grenade-throwers (‘Granatenwerfer’) which fired the stick grenades which were commonly used. Their medium trench-mortars were called mine-throwers (‘Minenwerfer‘). The heavy mortar was called the ‘Ladungswerfer’, which threw “aerial torpedoes”, containing a 200 lb (91 kg) charge to a range of 1,000 yd (910 m). The flight of the missile was so slow and leisurely that men on the receiving end could make some attempt to seek shelter.

Artillery dominated the battlefields of trench warfare. An infantry attack was rarely successful if it advanced beyond the range of its supporting artillery. In addition to bombarding the enemy infantry in the trenches, the artillery could be used to precede infantry advances with a creeping barrage, or engage in counter-battery duels to try to destroy the enemy’s guns. Artillery mainly fired fragmentation, high explosive, or, later in the war, gas shells. The British experimented with firing thermite incendiary shells to set trees and ruins alight. However, all armies had experienced shell shortages during the first year or two of World War I, due to underestimating their usage under intensive combat. This knowledge had been gained by the combatant nations in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 when daily artillery fire consumed ten times more than daily factory output but had not been capitalised on.

Artillery pieces were of two types: guns and howitzers. Guns fired high-velocity shells over a flat trajectory and were often used to deliver fragmentation and to cut barbed wire. Howitzers lofted the shell over a high trajectory so it plunged into the ground. The largest calibers were usually howitzers. The German 420 mm howitzer weighed 20 tons and could fire a one-ton shell over 10 km. A critical feature of period artillery pieces was the hydraulic recoil mechanism, which meant the gun did not need to be re-aimed after each shot.

Initially each gun would need to register its aim on a known target, in view of an observer, in order to fire with precision during a battle. The process of gun registration would often alert the enemy an attack was being planned. Towards the end of 1917, artillery techniques were developed enabling fire to be delivered accurately without registration on the battlefield – the gun registration was done behind the lines then the pre-registered guns were brought up to the front for a surprise attack.

Early World War I gases were unreliable, as they could easily be blown back on the troops that deployed them. There were three main agents used: mustard gas, chlorine, and phosgene. This prompted the use of gas masks. Early on, improvised gas masks were made by urinating on a handkerchief and putting it over their nose and mouth so the urea would disable the poison.

Tear gas was first employed in August 1914 by the French, but this could only disable the enemy. In April 1915, chlorine was first used by Germany at the Second Battle of Ypres. A large enough dose could kill, but the gas was easy to detect by scent and sight. Those that were not killed on exposure could suffer permanent lung damage. Phosgene, first used in December 1915, was the most lethal killing gas of World War I—it was 18 times more powerful than chlorine and much more difficult to detect.

However, the most effective gas was mustard gas, introduced by Germany in July 1917. Mustard gas was not as fatal as phosgene, but it was hard to detect and lingered on the surface of the battlefield and so could inflict casualties over a long period. The burns it produced were so horrific that a casualty resulting from mustard gas exposure was unlikely to be fit to fight again. Only 2% of mustard gas casualties died, mainly from secondary infections.

The first method of employing gas in World War I was by releasing it from a cylinder when the wind was favourable. Such an approach was obviously prone to miscarry if the direction of the wind was misjudged. Also, the cylinders needed to be positioned in the front trenches where they were likely to be ruptured during a bombardment. Later in the war, gas was delivered by artillery or mortar shell.

The Germans employed Flammenwerfer (flamethrowers) during the war for the first time against the French on 25 June 1915, then against the British 30 July in Hooge. The technology was in its infancy, and use was not very common until the end of 1917 when portability and reliability were improved. It was used in more than 300 documented battles. In 1918, it became a weapon of choice for Stoßtruppen (Stormtroopers) with a team of six Pionieren (pioneers, engineers) per squad.

During the first year of the First World War, none of the combatant nations equipped their troops with steel helmets. Soldiers went into battle wearing simple cloth or leather caps that offered virtually no protection from the damage caused by modern weapons. German troops were wearing the traditional leather Pickelhaube (spiked helmet), with a covering of cloth to protect the leather from the splattering of mud.

Once the war entered the static phase of trench warfare, the number of lethal head wounds that troops were receiving from fragmentation increased dramatically. The French were the first to see a need for greater protection and began to introduce steel helmets in the summer of 1915. The Adrian helmet replaced the traditional French kepi and was later adopted by the Belgian, Italian and many other armies.

At about the same time the British were developing their own helmets. The French design was rejected as not strong enough and too difficult to mass-produce. The design that was eventually approved by the British was the Brodie helmet. This had a wide brim to protect the wearer from falling objects, but offered less protection to the wearer’s neck. When the Americans entered the war, this was the helmet they chose, though some units used the French Adrian helmet.

The traditional German ‘pickelhaube’ was replaced by the Stahlhelm or “steel helmet” in 1916. Some elite Italian units used a helmet derived from ancient Roman designs. None of these standard helmets could protect the face or eyes, however. Special face-covers were designed to be used by machine gunners, and the Belgians tried out goggles made of louvres to protect the eyes. Additionally, tank crews were issued with or fashioned makeshift face masks to protect against the hot metal fragments that ricocheted around the compartment when the exterior of the tank was hit with machinegun fire.

The use of barbed wire was decisive in slowing infantry traveling across the battlefield. Slowed down by wire obstacles, they were much more likely to be hit by concentrated rifle and machinegun fire. Liddell Hart identified barbed wire and the machine gun as the elements that had to be broken to regain a mobile battlefield. Wiring was usually done at night, to avoid casualties in no man’s land. The screw picket, invented by the Germans and later adopted by the Allies during the war, was quieter than driving stakes, and thus helped decrease the amount of noise working parties would create. Methods to defeat it were rudimentary. British and Commonwealth forces relied on wire cutters, which proved unable to cope with the heavier gauge German wire. The Bangalore torpedo was adopted by many armies, and continued in use past the end of World War II.

The fundamental purpose of the aircraft in trench warfare was reconnaissance and artillery observation. Aerial reconnaissance was so significant in exposing movements, it has been said the trench stalemate was a product of it. The role of the fighter was to protect friendly reconnaissance aircraft and destroy those of the enemy, or at least deny them the freedom of friendly airspace. This involved achieving air superiority over the battlefield by destroying the enemy’s fighters as well.

Spotter aircraft would monitor the fall of shells during registration of the artillery. Reconnaissance aircraft would map trench lines, first with hand-drawn diagrams, later with photography, monitor enemy troop movements, and locate enemy artillery batteries so that they could be destroyed with counter-battery fire.

In 1917 and 1918, new types of weapons were fielded. They changed the face of warfare tactics and were later employed during World War II.

The French introduced the CSRG 1915 Chauchat during Spring 1916 around the concept of “walking fire“, employed in 1918 when 250,000 weapons were fielded. More than 80,000 of the best shooters received the semi-automatic RS

The French Army fielded a ground version of the Hotchkiss Canon de 37 mm used by the French Navy. It was primarily used to destroy German machine gun nests and concrete reinforced pillboxes with high explosive rounds, but an armour piercing round was designed to defeat the German tanks, making it the first anti-tank gun.

A new type of machine gun was introduced in 1916. Initially an aircraft weapon, the Bergmann LMG 15 was modified for ground use with the later dedicated ground version being the LMG 15 n. A. It was used as an infantry weapon on all European and Middle Eastern fronts until the end of World War I. It later inspired the MG 30 and the MG 34 as well as the concept of the general-purpose machine gun.

C 1917 rifle, allowing them to rapid fire at waves of attacking soldiers. Firing ports were installed in the newly arrived FT 1917 tanks.

What became known as the submachine gun had its genesis in World War I, developed around the concepts of infiltration and fire and movement, specifically to clear trenches of enemy soldiers when engagements were unlikely to occur beyond a range of a few feet. The MP 18 was the first practical submachine gun used in combat. It was fielded in 1918 by the German Army as the primary weapon of the stormtroopers, assault groups that specialised in trench combat.

The dry chalk of the Somme was especially suited to mining, but with the aid of pumps, it was also possible to mine in the sodden clay of Flanders. Specialist tunneling companies, usually made up of men who had been miners in civilian life, would dig tunnels under no man’s land and beneath the enemy’s trenches. These mines would then be packed with explosives and detonated, producing a large crater. The crater served two purposes: it could destroy or breach the enemy’s trench and, by virtue of the raised lip that they produced, could provide a ready-made “trench” closer to the enemy’s line. When a mine was detonated, both sides would race to occupy and fortify the crater.

If the miners detected an enemy tunnel in progress, they would often counter-mine and try to drive a tunnel under the enemy’s tunnel in which they would detonate explosives to create a camouflet to destroy the enemy’s tunnel. Night raids were also conducted with the sole purpose of destroying the enemy’s mine workings. On occasion, mines would cross and fighting would occur underground. The mining skills could also be used to move troops unseen. On one occasion a whole British division was moved through interconnected workings and sewers without German observation. The British detonated a number of mines on July 1, 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The largest mines—the Y Sap Mine and the Lochnagar Mine—each containing 24 tons of explosives, were blown near La Boiselle, throwing earth 4,000 feet into the air.

At 3.10 AM on June 7, 1917, 19 mines were detonated by the British to launch the Battle of Messines. The average mine contained 21 tons of explosive and the largest, 125 feet beneath Saint-Eloi, was twice the average at 42 tons. As remarked by General Plumer to his staff the evening before the attack:

“Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography.”

The craters from these and many other mines on the Western Front are still visible today. Two undetonated mines remained in the ground, with their location mislaid after the war. One blew during a thunderstorm in 1955; the other remains in the ground.

While trenches have often been dug as defensive measures, in the pre-firearm era, they were mainly a type of hindrance for an attacker of a fortified location, such as the ditch(or moat) around a castle. An early example of this can be seen in the Battle of the Trench.

Only with the advent of accurate firearms did the use of trenches as positions for the defender of a fortification become common. Elaborate trench and bunker systems were employed by the Māori to withstand British artillery barrages, poison-gas shells and bayonet charges during the New Zealand Wars in the 1840s. Trench systems were also employed in the Russo-Japanese War and American Civil War. The military usage evolved very quickly in the First World War, until whole systems of extensive main trenches, backup trenches (in case the first lines were overrun) and communication trenches had been developed, often stretching dozens of kilometres along a front without interruption, and some kilometres further back from the opponent’s lines.

The fundamental strategy of trench warfare in World War I was to defend one’s own position strongly while trying to achieve a breakthrough into the enemy’s rear. The effect was to end up in attrition; the process of progressively grinding down the opposition’s resources until, ultimately, they are no longer able to wage war. This did not prevent the ambitious commander from pursuing the strategy of annihilation—the ideal of an offensive battle which produces victory in one decisive engagement.

The Commander in Chief of the British forces during most of World War I, General Douglas Haig, was constantly seeking a “breakthrough” which could then be exploited with cavalry divisions. His major trench offensives—the Somme in 1916 and Flanders in 1917—were conceived as breakthrough battles but both degenerated into costly attrition. The Germans actively pursued a strategy of attrition in the Battle of Verdun, the sole purpose of which was to “bleed the French Army white”. At the same time the Allies needed to mount offensives in order to draw attention away from other hard-pressed areas of the line.

The popular image of a trench assault is of a wave of soldiers, bayonets fixed, going “over the top” and marching in a line across no man’s land into a hail of enemy fire. This was the standard method early in the war; it was rarely successful. More common was an attack at night from an advanced post in no man’s land, having cut the barbed wire beforehand. In 1917, the Germans innovated with infiltration tactics where small groups of highly trained and well-equipped troops would attack vulnerable points and bypass strong points, driving deep into the rear areas. The distance they could advance was still limited by their ability to supply and communicate.

The role of artillery in an infantry attack was twofold. The first aim of a bombardment was to prepare the ground for an infantry assault, killing or demoralising the enemy garrison and destroying his defences. The duration of these initial bombardments varied, from seconds to days. Artillery bombardments prior to infantry assaults were often ineffective at destroying enemy defences, only serving to provide advance notice of an attack. The British bombardment that began the Battle of the Somme lasted eight days but did little damage to either the German barbed wire or their deep dug-outs, where defenders were able to wait out the bombardment in relative safety.

Once the guns stopped, the defenders had time to emerge and were usually ready for the attacking infantry. The second aim was to protect the attacking infantry by providing an impenetrable “barrage” or curtain of shells to prevent an enemy counter-attack. The first attempt at sophistication was the “lifting barrage” where the first objective of an attack was intensely bombarded for a period before the entire barrage “lifted” to fall on a second objective farther back. However, this usually expected too much of the infantry, and the usual outcome was that the barrage would outpace the attackers, leaving them without protection.

This resulted in the use of the “creeping barrage” which would lift more frequently but in smaller steps, sweeping the ground ahead and moving so slowly that the attackers could usually follow closely behind it. This became the standard method of attack from late 1916 onward. The main benefit of the barrage was suppression of the enemy rather than to cause casualties or material damage.

Capturing the objective was half the battle, but the battle was only won if the objective was held. The attacking force would have to advance with not only the weapons required to capture a trench but also the tools—sandbags, picks and shovels, barbed wire—to fortify and defend from counter-attack. A successful advance would take the attackers beyond the range of their own field artillery, making them vulnerable, and it took time to move guns up over broken ground. The Germans placed great emphasis on immediately counter-attacking to regain lost ground. This strategy cost them dearly in 1917 when the British started to limit their advances so as to be able to meet the anticipated counter-attack from a position of strength. Part of the British artillery was positioned close behind the original start line and took no part in the initial bombardment, so as to be ready to support later phases of the operation while other guns were moved up.

A major difficulty faced by an attacking force in a trench battle was unreliable communications. Wireless communications were still in their infancy, so the available methods were telephone, telegraph, semaphore, signal lamps, signal flares, homing pigeons and runners. Messages frequently could not get through, or if they did, were out of date. A delay would pass when transferring news to the division, corps and army headquarters.

Consequently, the outcome of many trench battles was decided by the company and platoon commanders in the thick of the fighting. Senior commanders could not influence the battle for lack of information and inability to get orders to the troops. Opportunities were frequently lost because reinforcements could not be committed at the right time or place, and supporting artillery could not react to a changing situation.

Throughout World War I, the major combatants slowly groped their way towards various tactics aimed at breaking the stalemate of trench warfare, beginning with the French and Germans, with the British Empire forces also contributing to the collective learning experience. The Germans could reinforce their western front with additional troops from the east once Russia dropped out of the war in 1917. This allowed the German army to take units out of the line and to train them in new methods and tactics, such as those of the stormtroopers.

The stormtrooper methods involved men rushing forward in small groups using whatever cover was available and laying down covering fire for other groups in the same unit as they moved forward. The new tactics, intended to achieve surprise by disrupting entrenched enemy positions, aimed to bypass strongpoints and to attack the weakest parts of an enemy’s line. Additionally, they acknowledged the futility of managing a grand detailed plan of operations from afar, opting instead for junior officers on the spot to exercise initiative. These infiltration tactics proved very successful during the German 1918 Spring Offensive against Allied forces.

Conceived to provide protection from fire, tanks added mobility as well. As the Allied forces perfected them, they broke the stalemate. While not effectively employed at first, Allied tanks had tremendous effects on the morale of German troops in the closing stages of the war on the Western front. The average infantryman had no anti-tank capability, and there were no specialised anti-tank guns. Once the Allies began to use concentrations of tanks, they broke through German lines relatively easily and could not be dislodged through infantry counterattack.

During the last 100 days of World War I the Allied forces broke through the German trench system and harried the Germans back using infantry supported by tanks and by close air support. Between the two world wars these techniques and innovations were developed and described worldwide by people like B.H. Liddell Hart, J. Walter Christie, Charles de Gaulle, Cavalcanti de Albuquerque and Russian military theorists, among others. The Germans picked up such ideas, developed them further and later put them into practice as blitzkrieg during World War II.