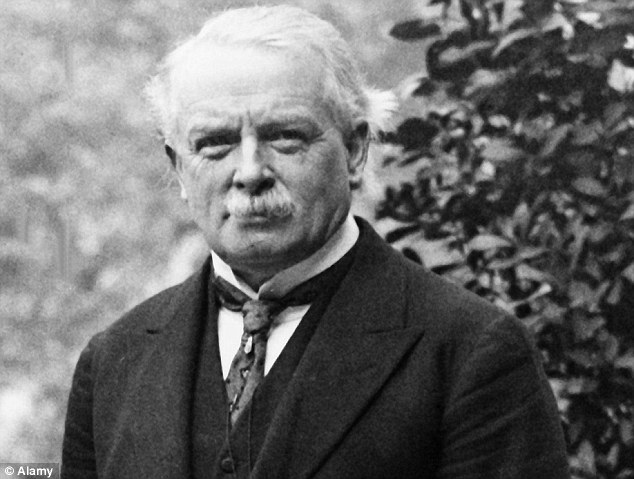

, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM KStJ PC (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was a British Liberal politician and statesman.

Although he was not raised in poverty, was considered to be a man of the people. Born in Manchester, he grew up in rural Wales with his mother and her brother, shoemaker and Baptist minister Richard Lloyd, His father had died when Lloyd George was a year old, so he adopted his uncle’s surname of Lloyd along with his own, George.

Through talent, hard work, and ambition, he became first a successful lawyer and then, in 1890, at the age of 27, the youngest member of the House of Commons at the time. He soon earned a reputation as a fiery radical, denouncing the hereditary privileges of the aristocracy and the militarism of the British Empire. As a leading member of the Liberal governments from 1906 he was at the forefront of social and political reform and known for the emotional eloquence of his speeches.

On a personal level, Lloyd George was no stranger to scandal. His secretary, Frances Stevenson, was his mistress, and in 1913 he was caught up in allegations of insider share trading in Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company. As Prime Minister, he sold honours and peerages for cash.

Lloyd George was instinctively aligned with the anti-war tradition of the Liberal Party. However, during the Agadir Crisis of 1911, when a visit by the German Kaiser to the Moroccan port was perceived as provocative by France and Britain, Lloyd George made a prominent speech advocating war if it was necessary to preserve Britain’s vital interests and prestige.

The German invasion of Belgium in August 1914 overcame any hesitations Lloyd George had about supporting the declaration of war. He established himself as the leading figure in a drive to mobilize the economy and, in May 1915, was the natural choice to head a new Ministry of Munitions. He bullied and bribed businessmen into turning factories over to war production, achieving an impressive increase of output. As an acknowledged radical, he was able to win acceptance from trade unions for “dilution” – the use of unskilled workers and women to do jobs previously restricted to skilled male workers.

Unlike old-fashioned Liberals like Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, Lloyd George had no scruples about government interference in business or violation of individual freedoms. In December 1916, he won the support of the Conservative and Labour parties to replace Asquith as Prime Minister, splitting the Liberal party.

He set about establishing a small war cabinet and expanded government control of national life in order to boost the war effort. Many areas of the economy, such as coal mining and merchant shipping, were taken over by the state for the duration of the war. New ministries were created to direct food production and labour.

Lloyd George was not always so successful in imposing his will on the generals conducting the war. Instinctively anti-militarist, he distrusted generals, while they regarded him as militarily ignorant. He sought an alternative to the slaughter on the Western Front, advocating a diversion of resources to Salonika or Italy. This was opposed by General Sir William Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and Field Marshal Douglas Haig commanding British forces in France. Lloyd George tried to undermine the generals, eventually ridding himself of Robertson in February 1918. But Haig proved immovable.

In his war memoirs, published in 1933, Lloyd George presents himself as the man consistently humane and right while the military leaders were brutal and foolish. But some of his claims – for example, to have been solely responsible for the introduction of the convoy system at sea in April 1917 – are now widely contested. He has been blamed for withholding troops from the Western Front in early 1918, as part of his private war with Haig. Leaving the British Army vulnerable to the German Spring Offensive.

Lloyd George won the post-war general election of 1918 partly by promising to make Germany pay reparations and to prosecute German war criminals, including the Kaiser. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, however, he tried to steer a course between French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau’s desire to permanently disable Germany and the idealism of US President Woodrow Wilson.

In domestic affairs he aspired to continue his pre-war radical reforms – he had set up a ministry for reconstruction as early as 1917 – but as the leader of a predominantly Conservative coalition had little scope for action. He returned to leadership of the Liberal Party from 1924, but that once great movement never recovered from the split he had engineered in 1916. In the run-up to World War II, Lloyd George admitted Hitler’s forceful leadership and favoured seeking peace in 1940. As a result, he had become an isolated figure in British public life by the time he died in 1945.