When the British Empire went to war on the 4th of August 1914 the Royal Navy was the strongest fleet in the world – but nearly all of its newest and most and most powerful warships were concentrated in Scapa Flow, hoping for a decisive showdown with the Imperial German High Seas Fleet in the North Sea. The remote British naval stations dotted around the world to safeguard the Empire’s long sea routes were necessarily entrusted to squadrons of old slow warships, many manned by untrained reservists, whose task it was to hunt down and destroy the German squadrons and individual surface raiders known to be at large.

On the 1st of November 1914 one of these ad hoc and ageing British squadrons was destroyed in an engagement known as the Battle of the Coronel. And the powerful, hard hitting German East Asiatic squadron, which had crossed the Pacific from China to fight this battle off the coast of Chile, was only brought to bay off the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic by the most prodigious efforts on the part of the British Admiralty

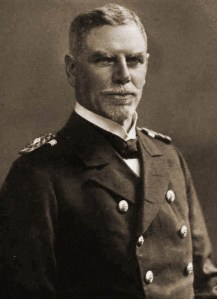

On the outbreak of war the biggest problem facing Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, commanding the North American and West Indies station, was the threat posed to British and French commerce by the new and fast German light cruisers Karlsruhe and Dresden. In the first week of the war Karlsruhe ran clean away from Cradock’s pursuing cruisers and escaped, continuing to operate in the southern Caribbean until her destruction by an internal cordite explosion on the 4th of November. Dresden vanished down the South Atlantic coast to prey on allied shipping in the South Atlantic. Cradock moved south in pursuit and on the 3rd of September was ordered by the Admiralty to stay in the South Atlantic and take command of the South East Coast of America station. His widely dispersed cruisers nevertheless failed to prevent Dresden from escaping into the Pacific on the 18th of September.

Only thirteen years after the first weak wireless signal had been transmitted across the Atlantic, the British and German Admiralties were beginning to appreciate the immense difficulty of coordinating the movements of warships on both sides of the world, acting on wireless and telegraph data which might either be out of date or simply wrong. The British, however, were labouring under self-created problems from which the Germans were largely free. The recently formed Admiralty War Staff was a cumbrous body with a chief-of-staff, Vice Admiral Sir Doverton Sturdee, who insisted on handling every important matter himself. Higher up, the British Admiralty was beset with the wide-ranging enthusiasms of the First Lord, Winston Churchill, and a First Sea Lord, Prince Louis of Battenberg, who was forced to resign on the 28th of October after a vicious press campaign objecting to his German birth.

As a result of all these inhibitions, the Admiralty was fatally slow in guessing the intentions of Vice Admiral Maximillian von Spee of the German East Asiatic Squadron, who had sailed from the German treaty port of Tsingtao before the outbreak of war and vanished into the Pacific. Though Spee detached one of his light cruisers, Emden, to embark on a brilliant lone commerce-raiding cruise in the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal, his own long-term plan was to fight his way home to Germany via Cape Horn after inflicting maximum damage to Allied trade in the Pacific and Atlantic, and forcing maximum inconvenience on the Allied navies.

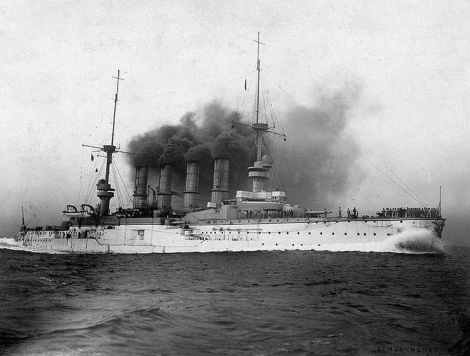

In total contrast to the ill-assorted scrapings which were to be sent against him by the British Admiralty, Spee commanded one of the elite gunnery squadrons of the German navy (his flagship, the armoured cruiser Scharnhorst, had won the Kaiser’s special prize for gunnery for two years running). In addition to Scharnhorst, Spee had her sister ship Gneisnau and the light cruiser Nürnberg. Another of his light cruisers, Leipzig, had been showing the flag off the North American coast before the war broke out and was still on the far side of the Pacific. She eventually re-joined the rest of Spee’s squadron at Eastern Islands – as did Dresden, which compensated for the earlier detachment of Emden.

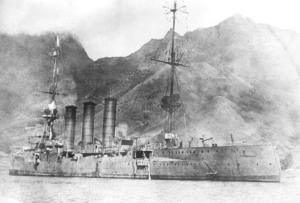

Spee’s voyage across the Pacific was guided by the need to ship coal at regular intervals, either by prearranged rendezvous with colliers or at shore coaling stations. His squadron steered from one German-controlled group of islands to the next. Spee moved from Pagan Island in the Marianas (11-13 August) to Eniwetok in the Marshalls (19-22 August), south-east to Christmas Island (7 September), south-west to Samoa (14 September), then east for an abortive attack on French Tahiti (22 September). From Tahiti the squadron headed north-east to the Marquesas group (26 September – 3 October) and finally south-east to Easter Island (12-18 October) where Spee was joined by Leipzig and Dresden.

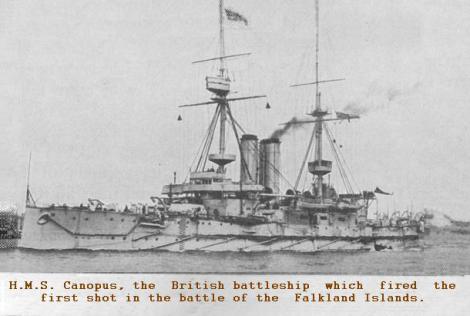

On the British side, it was a sad story of confusing and misleading signals between the Admiralty and Cradock: the Admiralty assumed that Cradock would not attack with an inferior force. Cradock assuming that the Admiralty had more information than he did. As early as the 14th of September Cradock heard from the Admiralty that there was a ‘strong possibility of Scharnhorst and Gneisnau appearing off the South American coast, that he was being sent the old battleship Canopus and the new cruiser Defence, the latter from the Mediterranean. Two days later, however, Cradock was told that Spee had been sighted steaming away from Samoa to the north-west, and that on the basis of this (erroneous) report, ‘two cruisers and an armed liner would appear sufficient for Magellan Straits and west coast’.

Cradock never did hear that Defence would not be joining him from the Mediterranean. What he did hear, from Captain Grant of the Canopus, was a mistaken report that the old battleship was unable to steam faster than 12 knots. He therefore decided to leave her behind and patrol the Southern Chilean coast with the light cruiser Glasgow, armed liner Otranto, and the ageing armoured cruiser Good Hope (Cradock’s flagship) and Monmouth.

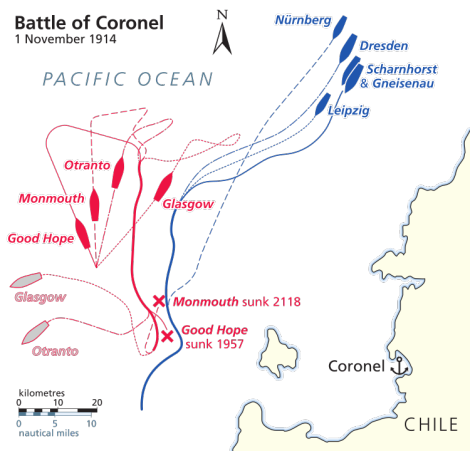

This, then, was the British force at sea off Coronel in the late afternoon of the 1st of November 1914, when at 4.40p.m. Glasgow sighted the one German warship which Craddock expected to find off the American coast: Leipzig. Within minutes, however, Craddock learned that Leipzig was not alone. Spee and his entire squadron were with her. When Spee’s cruisers hove in sight Cradock could have retired to the south to re-join Canopus, 400km (250mi) away, but he seems to have decided to force a close battle and do Spee’s ships as much damage as possible, knowing that they could find no friendly port in which to effect repairs to battle damage. In a strong wind and high sea, he turned to the south and formed line-of-battle, steering a course to converge with the line of Spee’s approach. He tried to get between Spee’s line and the coast but Spee turned away, leaving the British ships silhouetted against the setting sun and ‘afterglow’ while the German ships blended in with the deepening gloom of the evening to the east. This was a severe disadvantage for the British gunners, but it was the disparity in firepower which proved disastrous for the British. When Scharnhorst opened fire, shortly after sunset (7.00p.m.), Cradock’s line was within range of twelve German 8.2-inch guns, to which only Good Hope’s two 9.2-inch guns could answer.

Shooting superbly from their opening salvoes, the German ships plastered Cradock’s frail line with hits in the first ten minutes. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau hammered at Good Hope and Monmouth; Leipzig, less effectively, began to engage Glasgow; and Dresden bracketed Otranto, causing the latter to edge prudently out of the line and follow Cradock out of range of further shells. By 7.15p.m. Scharnhorst, with her third salvo, had knocked out Good Hope’s forward 9.2-inch turret and Gneisenau had inflicted similar damage on Monmouth.

As the range continued to narrow the British ships tried to hit back, but it was virtually impossible to see their fall of shot. By 7.35p.m. The range was down to 5000m (5500yrd) and the Germans were scoring so many hits on Good Hope and Monmouth that Scharnhorst’s spotting officer found it impossible to note them in sequence. Both the British armoured cruisers were blazing furiously; at 7.45p.m. Monmouth yawed out of the line, and five minutes later Good Hope was blasted by a terrible explosion between her main mast and after tunnel. She went down at about 8.00p.m., taking Cradock and all his crew with her.

Captain Luce of the Glasgow realised that the battle was lost. Otranto had prudently vanished into the darkness half an hour before, Monmouth was virtually dead in the water, and the German cruisers were free to overwhelm him with their combined fire. Hard though it was to leave Monmouth, Luce therefore disengaged and ran south, losing sight of his pursuers at 8.50p.m. About thirty-five minutes later, Captain Luce sadly counted the flashes of seventy-five shots as Nürnberg, Spee’s rearmost ship, completed the German victory by sinking Monmouth.

The British Admiralty, now with Lord Fisher as First Sea Lord, reacted to the appalling news of Coronel with an outburst of furious energy which had been totally lacking in the weeks before the battle. With the aid of the French and Japanese navies, the Pacific was sealed tight to make it suicide for Spee to remain there. Nearly thirty British warships, twenty-one of them armoured, were set in motion to hunt down Spee’s five cruisers. Above all, two 12-inch-gun battle-cruisers, Invincible and Inflexible, were taken from the Home Fleet and sent to the South Atlantic under Admiral Sturdee to make Spee’s destruction inevitable.

Spee’s movements after Coronel were unaccountably leisurely, given that his best chance of survival was a swift break into the South Atlantic before British reinforcements could reach the scene. He lingered off Valparaiso until the 14th of November and did not pass Cape Horn until the night of the 1st of December. The German ships coaled from their colliers on the 6th, and Spee made the fateful decision to commence operations in the Atlantic by attacking Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands. What he did not know was that Canopus had been anchored to protect the harbour with her 12-inch guns, and that Sturdee had just arrived with his two battle-cruisers and five cruisers (including Glasgow, the only British ship to serve in both actions).

When Spee was sighted approaching Port Stanley at 8.00a.m. On the 8th of December, the British fleet was coaling – but a spirited 12-inch broadside from Canopus caused Spee to turn and run. It took Sturdee’s force nearly two hours to raise steam and weigh, but by 10.00a.m. He was hard on Spee’s trail with both battle-cruisers and the cruisers Kent, Glasgow, Carnarvon and Cornwall. (The cruiser Bristol and the Macedonia, a converted liner, spent the day in rounding up and sinking Spee’s colliers Baden and Santa Isabel).

By 12.47p.m. Sturdee, flying his flag in Invincible, was close enough to open fire, echoed by Inflexible and Glasgow. Spee realised that his force was totally outgunned, and at about 1.20p.m. Bravely signalled to Nürnberg, Leipzig and Dresden to try to escape while he fought the British with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The German gunnery was excellent as it had been at Coronel, and the British were hampered by the obstruction of their own smoke; but the sheer weight of shell thrown by the British battle-cruisers meant that the issue was never in doubt. Fighting bravely to the last, both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau had been battered to wrecks by the time they sank. Scharnhorst at 4.17p.m. and Gneisenau at 6.00p.m. Only 190 survivors were rescued from Gneisenau out of her complement of about 800.

Meanwhile the British cruisers Kent and Cornwall raced on in pursuit of the fleeing German light cruisers. Dresden sheered off to the south-west and escaped, but Nürnberg was overhauled and sunk by Kent at 7.27p.m. and Leipzig followed at 8.35p.m. Dresden was finally trapped by Kent and Glasgow off the Chilean coast at Mas a Tierra and was scuttled to avoid capture on the 14th of March 1915. The British revenge for Coronel was complete.

References

- Robert Massie (2004). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-04092-8.

- Barrie Pitt (1960). Coronel and Falkland. London: Cassell.

- Arthur Marder (1961–1970). From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow (5 Vols). London: Oxford University Press.

- “Good Hope Sunk”. The Times (40689). 7 November 1914. p. 9.

- Winston Churchill (1923–1927). The World Crisis (four Volumes). London: Thornton Butterworth.

- Gerhard Wiechmann (2004). Vom Auslandsdienst in Mexiko zur Seeschlacht von Coronel. Kapitän Karl von Schönberg. Reisetagebuch 1913–1914 (From foreign service in Mexiko to the sea battle of Coronel. Captain Karl von Schönberg. Voyage diary 1913–1914). Bochum: Dr. Winkler Verlag. ISBN 3-89911-036-6. ISBN 978-3-89911-036-4.

- Norman Friedman and A.D. Baker (2008). Naval Firepower: Battleship Guns and Gunnery in the Dreadnought Era. Naval Press Institute. ISBN 1-59114-555-4.

- Arthur Herman (2005). To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-053424-0.

- Michael McNally (2012). Coronel and Falklands 1914; Duel in the South Atlantic. Osprey Campaign Series No. 248. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781849086745