The Battle of Lissa on July 20, 1866, in which Austrian Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff won a decisive naval victory over a numerically superior Italian foe, is typically celebrated as the greatest maritime event in the history of the Habsburg Empire, but ironically it also marked the beginning of some of the most stagnant years in the history of the kaiserlich–königlich (k.k.) Kriegsmarine (known as the kaiserlich und königlich [k.u.k.] Kriegsmarine after 23 October 1889). When peace was made with Italy on October 3, 1866, official interest in Habsburg naval power rapidly waned. One of the reasons for this was the establishment of the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary in 1867, which gave a Hungarian parliament in Budapest an equal say in the governing of the empire.

Since the Hungarian half of the Empire had minimal manufacturing capability and little interest in overseas trade, the Hungarian parliament almost always refused to grant new funds for Imperial Naval construction and expansion. The cause of naval expansion took another serious blow in1882 when, politically, Italy was no longer seen as a potential naval rival after the Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy was formed. With no prospect of naval war on the horizon and Hungarian refusal to maintain a modern fleet, which it considered unnecessary and not pertinent to Hungarian interests, the k.k. Kriegsmarine languished with a motley collection of old casemate battleships and only a sliver of the Empire’s annual defence budget.

The lack of funding pushed the Austrian naval leadership, particularly Admiral Maximilian Daublesky von Sterneck, to pursue a minimal fleet program of smaller torpedo vessels inspired by the Jeune École, As the Captain of Tegetthoff’s flagship at the Battle of Lissa, Sterneck also clung to the idea that ramming a more powerful opponent was still a viable combat tactic.

As the theories of the Jeune École were laid to rest by the increasing size and more effective guns of the first modern battleships, the k.k. Kriegsmarine found itself woefully outclassed compared to other navies. Even the veterans of Lissa came to realise that the future of naval combat lay in the long-range naval rifle instead of the ram bow. Under the tenures of Admiral Hermann von Spaun and Admiral Rudolf Graf von Montecuccoli degli Erri, and with the backing of the naval-minded heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the k.k. Kriegsmarine experienced, in its own unique way, a modern naval renaissance beginning at the turn of the century.

Influenced by the theories of Alfred Thayer Mahan and the concept of a “fleet-in-being,” these leaders realized that a fleet made up of modern battleships was necessary to protect not just the hundreds of miles of coastline of the Empire but also the growing domestic maritime industries and overseas commerce against the increasing threat of Italian irredentism. By the beginning of World War I, despite intense domestic political opposition, draconian budget limitations, and the use of extralegal means, the K.u.K. Kriegsmarine possessed a compact but powerful force of modern battleships.

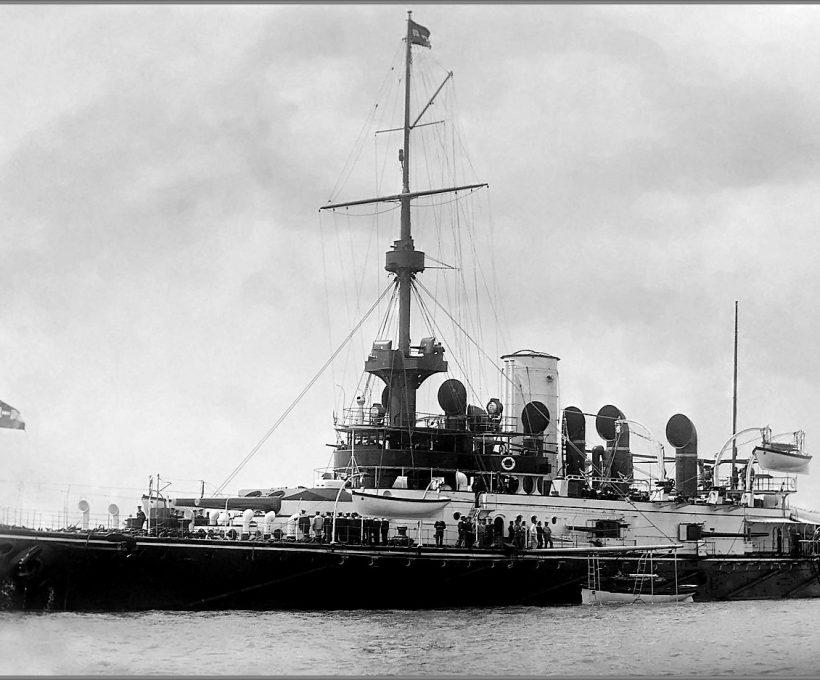

Monarch Class

As the navies of the world’s Great Powers gradually accepted as standard the pre-dreadnought configuration for their battleships throughout the 1890s, even Admiral Sterneck felt compelled to compromise his adherence to the Jeune École and the strategies of Lissa, and follow international developments. In 1892he requested funds for the construction of a class of three identical coastal defense battleships. The designer of the resulting Monarch Class was General Schiffbauingenieur Siegfried Popper, who would design all of the Austro-Hungarian battleships and dreadnoughts that served in World War I.

After studying engineering at universities in Prague and Karlsruhe, Popper joined the k.k. Kriegsmarine in 1869 as an assistant engineer and eventually worked his way up into the design and construction department. In 1907 he retired as head of the 1stDepartment of the Navy Technology Committee. His first experience was supervising the construction of the torpedo cruisers Panther and Leopard, built by Armstrong Mitchell & Company in Great Britain, but he was eventually called upon to prepare designs for a new class of coastal defense ships. For the rest of his career, Popper faced the arduous task of trying to design powerful battleships under what were probably the most strictly limited budgets enforced upon a navy by any of the Great Powers. He would design five different battleships classes under these conditions over the course of two decades.

The Monarchs somewhat resembled monitors with their low freeboard but this was offset by the large superstructure between the primary turrets. They were also the first Austro-Hungarian battleships to have enclosed primary gun turrets. The first of the class, SMS Wien, was laid down at the Trieste shipyard of Stabilimento Technico Triestino (STT) on February 16, 1893, followed there by SMS Monarch on July 31. SMS Budapest was laid down at the Pola Navy Yard on February 16, 1893. Wien was commissioned on May 13, 1897, followed by Monarch on 11 May, 1898, and Budapest on May 12, 1898. The Monarchs had a displacement of 5,547 metric tons. They were 97.7m long at the waterline, 17m wide at the beam, and had a maximum draft of 6.4m. Ship’s complement was 26 officers and 397 ratings.

The big gun selected for the main turrets of the Monarch Class was the 24cm (9.5in) Krupp L/40 C/94 gun, designed in 1894. Two were mounted within the fore and aft main turrets and had an elevation range of -4 degrees to +25 degrees. With skilled crews, each gun could fire a round every three to four minutes. Every gun had its own manually operated ammunition hoist and the shells were pushed into the run with a pneumatically powered rammer. Each of the main turrets required a crew of 20 sailors, and each ship could carry a total of 160 24cm (9.5in) high-explosive and 160 24cm (9.5in) armour-piercing shells.

As Krupp cemented steel plate came to replace Harvey steel plate, the armour-piercing capabilities of these guns were much reduced . From 10,000m only 12cm (4.7in) of Krupp cemented plate could be penetrated as opposed to 18cm (7in) of Harvey plate from the same distance. This limited the Monarchs to primarily shore bombardment operations during World War I.

Secondary armament consisted of six 15cm (6in) Škoda L/40 guns mounted in casement turrets in the hull, three on each side of the ship. They could fire four to five rounds per minute and had an elevation range of -7 degrees to +20 degrees. Based on a Krupp design, these were the first pieces of heavy naval artillery made by the Škodawerke A.G. at Pilsen. For protection against torpedo boats, the Monarchs each mounted ten 4.7cm (1.8in) Škoda L/44 and four 4.7cm (1.8in) Hotchkiss L/33 quick-fire guns, which could fire up to 30 shells per minute with a maximum range of over 3,600m, and one Škoda M1893 8mm machine gun. Two 7cm (2.75in) Uchatius L/15 bronze-steel boat cannons were provided for use with landing parties.

Wien and Monarch were later equipped with a single 7cm (2.75in) Škoda L/50 K 10 BAG antiaircraft gun in 1917. Finally, each ship mounted two 450mm broadside torpedo tubes and carried four 450mm torpedoes, each possessing a 59kg (130 pounds) explosive charge.

The Monarchs were armoured with nickel-steel plate manufactured by the Witkowitzer Berbau und Eisenh üttengewerwerkschaft (Witkowitz Mines and Iron Works) in Moravia. The armored belt was thickest amidships at 270mm between the turrets, tapering to 220mm along the barbettes, and then gradually reducing to 120mm up to the bow. The casemate was protected by 80mm of armour; beneath the belt it was 180mm thick. The primary turrets were protected by 250mm of armor and the conning tower by 220mm. The horizontal deck armor was 40mm thick.

Monarch and Wien had five cylindrical boilers and two vertical four-cylinder triple-expansion engines powering two shafts that drove two propellers, each with three 4.42m diameter blades. These engines gave the ships 8,500 indicated horsepower and a maximum speed of 17.5 knots. Budapest had similar engines but these were fired by 16 Belleville water tube boilers that allowed the engines to generate 9,100 indicated horsepower, giving the ship a maximum speed of 17.8 knots.

Water tube boilers were smaller than previous cylindrical boilers and could be dismantled. Being substantially lighter, they also saved substantial weight that could be used for heavier armament or armor. Their main advantage, however, was their ability to change the flow of steam to the engines much more quickly, allowing for more rapid changes in speed. After Budapest, all subsequent Austro-Hungarian battleships would be equipped with water tube boilers. Supplied with a maximum load of coal at 500 tons, the Monarchs had a range of 3,500 nautical miles at 9 knots.

At the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, the three ships of the Monarch class were serving as the V Battleship Division, deployed as coastal defense ships. They also served as training ships, and were used to bombard coastal positions during the early years of the war. In August 1914, Budapest was transferred from Pula to Cattaro to shell Mount Lovcen. On 9 August 1914 Monarch shelled the French radio station at Budva. She also bombarded the Montenegrin radio station off Bar on 17 August and another station off Volovica Point on 19 August where she attacked the local radio station and barracks. Following these operations, Monarch served as a harbor defense ship. On 28–29 December 1915 Budapest supported the cruisers and destroyers of the Austro-Hungarian Navy that were to raid Durazzo, but the detachment returned to port without having opened fire on the enemy. On 9 January 1916, Budapest again bombarded the fortifications on Mount Lovcen, and helped to capture the enemy-held mountain. In late 1917 Budapest and Wien were sent to Trieste, and participated in shelling Italian troops in the Gulf of Trieste. On 10 December 1917, two Italian torpedo boats managed to penetrate the port of Trieste undetected, and fired torpedoes at the battleships Budapestand Wien. The torpedo fired at Budapest missed, but Wien was hit twice and sank in less than five minutes in the shallow water of the Trieste harbor. Forty-six men serving on Wien were killed in the attack. Budapest was subsequently given the task that Monarch had been performing for over three years, and was demoted to a floating barrack for German U-boat crews. In June 1918 Budapest was renovated and had a 380 mm (15 in) L/17 howitzer installed in her bow to use for coastal bombardment, but she never saw action with the new gun in place. At the end of the war in 1918, the remaining Monarch-class battleships, Budapest and Monarch, were handed over to Great Britain as war reparations. In 1920 the two ships were sold for scrap to Italy, and were broken up between 1920 and 1922.